This post is part of a series of evidence summaries for the 21 for 2021 project, a CREATe project within the AHRC Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC). The 21 for 2021 project offers a synthesis of empirical evidence catalogued on the Copyright Evidence Portal, answering 21 topical copyright questions for the 21st century. In this post, Joshua Yuvaraj (PhD Candidate (under examination), Monash University) and Rebecca Giblin (ARC Future Fellow and Associate Professor, Melbourne Law School) explore the empirical evidence relating to reversion rights.

This post is part of a series of evidence summaries for the 21 for 2021 project, a CREATe project within the AHRC Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC). The 21 for 2021 project offers a synthesis of empirical evidence catalogued on the Copyright Evidence Portal, answering 21 topical copyright questions for the 21st century. In this post, Joshua Yuvaraj (PhD Candidate (under examination), Monash University) and Rebecca Giblin (ARC Future Fellow and Associate Professor, Melbourne Law School) explore the empirical evidence relating to reversion rights.

Introduction

Creators are often required to make broad grants of copyright (e.g., all rights, worldwide, for the entirety of the copyright term) to book and music publishers, record labels and other cultural investors in exchange for getting their works produced and made available.

The consequences can be problematic. Those rights are usually transferred before the work enters the market, i.e., before anyone knows what they’re worth, which may result in the creator receiving unfairly low compensation. Additionally, while the investor no doubt hopes the work will enjoy blockbuster success, almost all cultural artifacts depreciate quickly, and these long grants can far outlast commercial interest in the work. When rights remain locked up in those circumstances, it can be impossible for creators to take advantage of alternative exploitation opportunities, as well as exacerbating the problem of orphan works.

Reversion rights entitle creators to reclaim their rights, enabling them to pursue new exploitation opportunities and, ideally, to make their works once again available to the public.

Debates and recent evolutions

There are three ways in which rights may revert: via contractual rights, statutory rights, or private agreement.

Reversion rights predate even modern copyright – the earliest contractual reversion clause we have located is from 1694. 1710’s Statute of Anne had a reversion right built in: rights went to authors for 14 years, and they got a fresh grant of 14 more if they were still alive after that. Bently and Ginsburg (2010) have found that, while it appears this structure was intended to benefit authors, in practice publishers often sought to obtain copyright from authors in its entirety, in some cases even seeking to bypass the reversionary term or give it to the publishers (pp. 1502-1507).

Author associations have for decades campaigned for stronger reversion rights, including a recent international campaign led by the International Authors Forum seeking more effective reversion clauses in contracts.

There has also been a growing focus on the potential benefits of statutory reversion rights in recent years.

Currently, more than half the world’s countries have some variety of reversion right enshrined in their copyright statutes. However, many of these do not take full advantage of the opportunities created by digital technologies and the internet for more efficiently reverting rights and maximising the opportunities for subsequent exploitation.

The 2019 Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market required EU Member States to implement a ‘use-it-or-lose-it’ rights for creators and performers, enabling them to reclaim unexploited rights (Art 22). In Canada, two parliamentary committees recommended new creators’ rights that would enable them to reclaim or automatically regain rights (even if they were still being exploited) 25 years after transfer. And in 2019, South Africa’s Parliament passed a bill containing a mandatory 25-year limit on copyright assignments for literary or musical works (s 23). President Cyril Ramaphosa ultimately refused to sign it into law due to concerns about whether it complied with South Africa’s constitution, and creators, activists and policymakers are working towards a replacement.

The advocacy for improved contractual and statutory reversion rights is predominantly motivated by the desire to protect creators in unequal bargaining positions by giving them a chance to regain unused rights and fairly participate in the success of their works. However, reversion rights can also assist copyright’s access aims by returning works to public circulation.

Existing evidence and research agendas

A search for ‘reversion’ and ‘termination’ on the Copyright Evidence portal revealed research on both contractual and statutory reversion rights.

Contractual reversion rights

Findings by Kretschmer, Gavaldon, Miettinen and Singh (2019) and Johnson, Gibson, and Dimita (2012) suggest contractual reversion rights continue to have widespread use and utility. Kretschmer et al. found just over half of ‘primary occupation authors’ had a reversion clause in at least one of their contracts. Twenty-three per cent of ‘primary occupation authors’ had used a reversion clause in the five years prior, and 29% reported additional income ‘either from a new publisher or through self-publishing’. These figures were broadly consistent with earlier results from Johnson, Gibson, and Dimita, although the latter reported a slightly higher percentage of authors exercising their reversion rights (38%) and earning income following reversion (70%). Kretschmer et al. suggested those who use reversion clauses and earn income following reversion tend to be higher-earning authors, but emphasised there was not necessarily a causative link between either of these factors.

Meanwhile, we (Yuvaraj and Giblin (2021)) conducted a longitudinal study examining 50 years of publishing contracts sourced within the archive of the Australian Society of Authors. We found these contracts very often took broad rights (e.g., all languages and all territories) for the entire copyright term, which could be 100 years or more. The extent of rights taken makes it particularly important to enshrine effective reversion rights to cover the likely event of the publisher losing commercial interest in the title while it’s still under copyright.

Our analysis found that, while reversion clauses were commonly present, they were often inadequate, ambiguous or outdated. “Out of print” clauses were particularly problematic, typically requiring books to be entirely unavailable before rights could be reverted. In the print era this was justifiable, as the book’s unavailability would be a clear indicator of the publisher’s unwillingness to make the sizeable investment necessary for a fresh print run. In the digital era, however, books may be technically “available” (e.g., as ebooks or via print on demand) even where publishers are no longer meaningfully investing in their success. Outdated formulations based on mere technical availability will prevent authors from regaining their rights over effectively unexploited works. These problems persisted well into digital-era contracts. However, even if these clauses were drafted in accordance with best practice, the fact the contracts last for so long means they are ill-equipped to respond to changes that might occur in the future. We concluded this meant there was a strong case for minimum statutory reversion rights, operating independently of contracts.

Statutory reversion rights – the US termination rights

One of the most hotly debated statutory reversion models is the US termination system. Under this system, creators can terminate copyright assignments after 35 years (or another period depending on the type and date of the grant).

Most recently, we (Yuvaraj, Giblin, Russo-Batterham and Grant (2021)) released a paper (forthcoming in the Journal of Empirical Legal Studies) and accompanying datasets investigating use of the US termination rights. We used computational methods to extract, clean, and analyse data from the US Copyright Office Catalog, where records are uploaded when a creator attempts to exercise their termination rights. The datasets, codebooks, and search phrases used are openly available and are designed to foster continued interrogation of the termination rights.

We also documented several interesting trends on the use of the termination right. For example, termination notices in relation to post-1978 rights grants for books tended to be filed by famous authors such as Francine Pascal, Ann M Martin, and Stephen King, suggesting few authors see value in formally terminating their rights after 35 years. Additionally, record labels contested the most attempted terminations (indicating ongoing disputes about whether recording artists can regain their rights in sound recordings).

A study by Heald (2017a) also highlights the potential impacts of the US termination rights on book availability. Using multiple samples of either New York Times bestsellers or books that had been reviewed by the New York Times Book Review, Heald concluded that books tended to be more ‘in print’ if they could be terminated under either of the two statutory termination provisions. Further, Heald concluded that a ‘one-time’ reversion of ebook rights to authors from the decision Random House v Rosetta Books had ‘an even greater effect on inprint status than the statutory schemes.’

Statutory reversion rights – the Imperial and Canadian approaches

Heald has also conducted empirical research into reversion rights both proposed and in force in Canada, the UK, and South Africa. The Copyright Act 1911 (UK) imposed an automatic reversion of copyright assignments and licences to an author’s estate 25 years after the author’s death (s 5(2)). While it was removed in the UK and other parts of the British Commonwealth later in the 20th century, Canada retained it Copyright Act, RSC 1985, c C-42, s 14(1)). In South Africa (Heald 2020b), Heald found a ‘statistically insignificant’ difference in the print status of books which had reverted under this provision versus books which had not. In the UK (Heald 2020a), Heald found ‘9% [of the studied works] were brought back into print by an independent press and made newly available 25 years or more after the author’s death.’ He also found similar results in Canada (10.4%) (Heald 2020a), although he noted that in Canada ‘copyrights [can] revert to authors early when a publisher declares bankruptcy’.

Other research

The other papers uncovered by the search were by Towse (2018) and Flynn, Giblin and Petitjean (2019). Towse’s paper is a useful primer on how reversion interacts with the economics of creative industries. Meanwhile, Flynn, Giblin and Petitjean’s research suggests the assumption that works will be ‘underused’ if copyright terms are not extended is not borne out. In fact, the authors show how lengthy terms are counterproductive to the widespread availability of works, strengthening the case for authors to have effective reversion rights.

Future directions for research

Reversion rights have immense potential for creators and performers to take advantage of new opportunities and for previously dormant works to be made available to the public. Further empirical research building on the work featured in the Copyright Evidence Portal will help policymakers develop reversion systems that better achieve these goals.

Scholars could conduct empirical research into the use and operation of reversion laws around the world, as Yuvaraj et al (2021) and Heald (2020a, 2020b) have begun to do for the US, Canadian and UK models. The various methods used in the research on the portal (surveys, content analysis of documentary evidence, scraping and automated analysis of large-scale datasets, etc.) offer models for exploring the various data on how reversion rights are being exercised.

Research into how works are used after reversion can help policymakers refine reversion systems. Scholars could, for instance, track the sales of books in print and electronic formats and library lending trends to help ascertain the economic and cultural effects of reversion.

Additional research into reversion by private agreement would be valuable too. Creators can regain their rights in the absence of contractual or statutory reversion rights if rightsholders such as publishers agree to release them, and work by the Authors Alliance shows that this is an alternative to exercise of formal reversion rights. The presence of contractual or statutory reversion rights could also help motivate publishers to privately negotiate the return of rights or subsequent exploitation agreements. More empirical research, using qualitative methods such as surveys and interviews, can help us more comprehensively understand the effects of formal reversion rights.

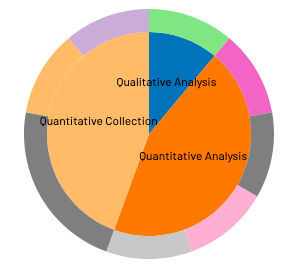

Pie chart visualisation from Copyright Viz showing skew towards quantitative methods of collection and analysis in empirical studies of reversion rights

Reversion rights have immense potential to reduce the collateral damage of copyright transfers that outlast rightholders’ commercial interest. Creators can benefit from additional exploitation opportunities, financial rewards and recognition. The public can benefit from access to works that could otherwise have been lost. A growing body of empirical research methods is exploring the use and impacts of reversion rights in contract and statute, demonstrating both the potential positive impacts of reversion rights and shortcomings of existing systems. Further research would enhance the ability of policymakers to tailor reversion schemes that maintain incentives for investment whilst better serving the interests of creators and the public.

This work has been supported by funding from the Australian Research Council as part of the Author’s Interest Project (FT170100011). This work also draws from Joshua’s PhD research, which was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program (RTP) Scholarship, a Monash University Graduate Excellence Scholarship, and the Australian Research Council through the Author’s Interest Project.