This post is part of a series of evidence summaries for the 21 for 21 project, a CREATe project within the AHRC Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC). The 21 for 21 project offers a synthesis of empirical evidence catalogued on the Copyright Evidence Portal, answering 21 topical copyright questions for the 21st century. In this post, Magali Eben (Lecturer, University of Glasgow) synthesises the empirical evidence relating to copyright’s relationship with competition law.

This post is part of a series of evidence summaries for the 21 for 21 project, a CREATe project within the AHRC Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC). The 21 for 21 project offers a synthesis of empirical evidence catalogued on the Copyright Evidence Portal, answering 21 topical copyright questions for the 21st century. In this post, Magali Eben (Lecturer, University of Glasgow) synthesises the empirical evidence relating to copyright’s relationship with competition law.

Introduction: the intersection of copyright and competition (law)

In the Anglo-American tradition, copyright plays an economic role, incentivising the production and distribution of creative work, by rewarding the creators and publishers of those works. In the continental European tradition, copyright protection (also) protects the personal link between the work and the individual who created it, by granting ‘moral rights’ to the author, such as the right to be recognised as the work’s creator and the right to preserve the integrity of the work. (Brown, Kheria, Cornwell, and Iljadica, 2019, 42)

The first rationale in particular strikes a chord with competition lawyers. After all, competition law is intended (inter alia) to protect competition on the market, and in doing so ensure an efficient allocation of resources. Traditionally, the focus here has been on price and so-called ‘static efficiency’ – ensuring that goods or services are produced at low cost, and optimally distributed (productive and allocative efficiency, respectively). Yet competition law also values ‘dynamic efficiency’: particularly in the last decade, but even before that, there has been a concern with incentivising the creation of improved or new products.

Competition law is concerned with the benefits of competition to society and thus, conversely, with the abuse of market power. In the ‘ideal’ models, perfect competition is the goal, and monopoly (unilateral market power) and collusion (where companies conspire to collectively use market power) the antitheses.

Copyright and competition law appear to work towards a common goal – incentivising new creations which can be commercialised. They address market failures, encouraging production which is beneficial to society. Despite these similarities, copyright and competition law are quite different: competition law does not look to incentivise individuals by giving them exclusive rights, but remedies conduct by powerful market participants which undermines the proper functioning of the competitive market. The assumptions of competition law – that plurality of sellers or, at least, ease of entry into a market are the best guarantees for the effective supply of goods and services – may seem contrary to the granting of exclusive rights in copyright. It would seem likely, then, that there would be an abundance of empirical research on interactions of copyright and competition law.

Existing evidence and research agendas

Studies which consider competition law

The empirical research in the Evidence Wiki is extensive. Yet, despite this amplitude and despite the overlaps between copyright and competition law, only a handful of papers explicitly discuss competition law. These are interesting papers: they apply competition law to copyright-related markets (see, for example, Max Planck Institute (2013)).

Some authors argue that competition law may address current power imbalances, or argue that competition law could prevent further concentration which results from copyright law or occurs in specific creative markets. Towse (2017) notes that competition law may be needed to address further concentration in the music industry.

There are some studies which rely on competition law as a cure for the problems copyright law cannot fix. Guibault, Westkamp and Rieber-Mohn (2007)’s study, for example, found that the technological protection measures are used to protect business models rather than content, thus perverting the purpose of the Infosoc directive. However, they put forward that this would be better solved by consumer and competition law than by copyright law. In another interesting study, Cuntz and Bergquist (2020) discuss various competition law solutions to address the market failures identified in their study on video-on-demand platforms.

Two studies stand out for their different approach. One study does not merely look at competition law at the end as the solution for problems identified in a copyright-focused study, but immediately applies competition law to a creative industry. Geradin (2005) looks at more specific competition law issues raised by access to premium content (essentially blockbusters and football rights) by content delivery operators with a special emphasis on new media platforms. Another study discusses competition law as a solution, which can not fully fill the gap left by a limited application of IP law. La Diega (2019)’s empirical study led to some fascinating conclusions on the relevance of IP law to the fashion industry, where complaining about IP infractions or relying on contracts is socially frowned upon. As the fashion industry is mostly guided by social norms, a move to transform it into an IP-intensive industry may not be successful. The author explains that the industry is affected by an imbalance of power. Whereas IP and contract law may not be useful in rebalancing existing relationships, the author asks whether competition law could be used to rebalance power, once the relationship is over. The author rightly acknowledges the limitations of an ex post approach, and of the decisions adopted in specific competition law cases.

Studies of interest to competition (law)

It may be surprising that so few papers in the Wiki refer to competition law. However, many other studies have findings which are relevant to competition law, despite not explicitly referring to the law itself. A fundamental issue identified in the Wiki is the effects of copyright protection on industry structure (e.g. oligopolies; competition; economics of superstars; business models; technology adoption). This issue is identified in 258 papers in the database. Upon further inspection, the findings of around 100 of these studies would be of clear interest to competition lawyers.

The effect of copyright on industry structure is very pertinent to competition law, particularly where these exclusive rights lead to ‘winner-take-all’ markets or exacerbate concentration in certain industries. In these circumstances, the risk of anti-competitive conduct increases. A couple of studies in the Wiki find that IP rights increase concentration in a market, and even create monopolies (e.g. Albinsson (2013), DiCola (2013)), which prompts certain authors to consider alternatives to IP rights (e.g. Shavell and van Ypersele (1999)). It is important to remember that the mere existence of market power is not a violation of competition law: however, market power is a prerequisite for most harm to competition, so that caution may be advised if copyright increases market power. As opposed to Towse’s paper, mentioned earlier, the other papers in the Wiki do not explicitly consider whether competition law could be used at a later stage to counterbalance the negative effects of increased concentration.

The studies in the Wiki looking at the impact of copyright duration on the production of creative goods are also interesting for competition lawyers (e.g. Png and Wang (2006), Pollock (2009), Rappaport (1998)), because the findings shed light on whether exclusive rights may increase or reduce the supply of products in a market. Within these papers, the focus is predominantly on value capture and profitability, and compensation for creative firms, which is supposed to incentivise the production of creative products. Both competition law and copyright are concerned with the production and supply of goods and services, and both areas of law assume that monetary reward will spur this supply. However, as we noted above, copyright law’s premise is that exclusive rights are needed to ensure the monetary rewards which incentivise individuals. Yet not all studies in the Wiki find that exclusive rights are necessary for compensation and profitability (see, for example, Erickson (2018)). Moreover, the rate of profitability and the distribution of rewards in a creative market does not automatically lead to increased product diversity or innovation benefitting consumers, nor does it necessarily translate into lower prices for consumers.

On the contrary, there are studies in the Wiki which find that, in particular contexts, exceptions are needed to copyright protection (technologies), in order to increase competition and enhance welfare (see, for example, Gasser (2004)).

A trend is discernible in the Wiki, in favour of studying the effect of piracy and file-sharing on a market. While early studies found that unrestricted copying may reduce the long term production of goods (Johnson (1985), Teece (1986)), some studies found that unauthorised copying, piracy and file-sharing may actually have positive effects on revenue in a market, on efficiency and prices, on the dissemination of creative products, on consumed product variety, or on innovation (e.g. Peukert, Claussen and Kretschmer (2015), Savelkoul (2019), Takeyama (1994), Van Eijk, Poort and Rutten (2010), van Roessel and Katzenbach (2018)). Not all studies arrive at the same conclusions, as some note that that file-sharing or relaxing copyright protection may adversely impact welfare (Mustonen (2005)) or that its effect on welfare is mixed or unclear (Liu (2014)), Peitz and Waelbroeck (2006), Zentner (2010)). In fact, there are studies which conclude that the effects vary depending on the size and initial popularity of firms: while Bhattacharjee, Gopal, Lertwachara, Marsden and Telang (2007) actually found that file-sharing does not hurt the survival of top-ranked albums, but does have a negative impact on low-ranked albums; other studies (e.g. Blackburn (2004) and Handke (2011)) found that file-sharing reduces the sales of incumbents, while benefitting unknown artists. This could benefit consumers by enhancing the dissemination of new or previously less well-known work.

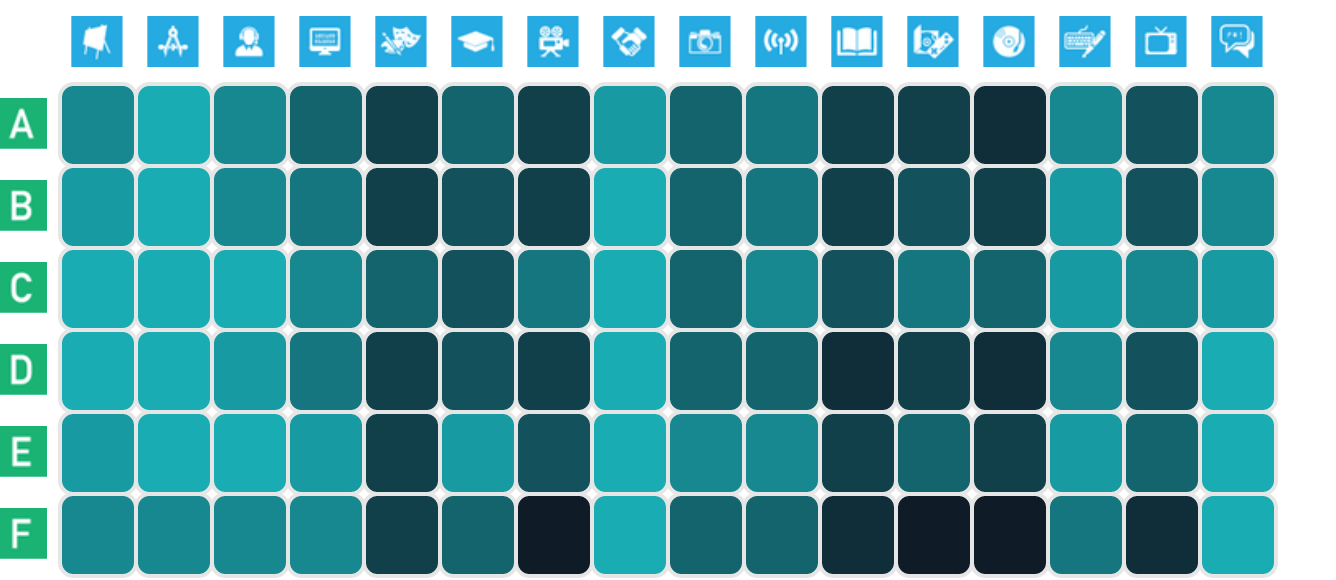

Figure 1: Heatmap distribution of Evidence Wiki studies by industry and policy issue

Of course, not all creative industries are the same. Several studies in the Wiki focus on a specific industry – such as music, games, video, TV, fashion. At times, these studies find that results in a particular industry may be peculiar compared to conventional wisdom derived from other industries (see, for example, Raustiala and Sprigman (2006) on the fashion industry). Competition lawyers are used to applying general assumptions to specific industries: analyses of anti-competitive conduct always take place in a relevant market. These industry-specific studies could provide useful background information to competition authorities. However, the concept of an ‘industry’ may not be the same as that of a relevant market in competition law, which focuses on identifying substitute products within the context of specific allegations (see Eben, The Antitrust Market Does Not Exist: Pursuit of Objectivity in a Purposive Process). There are studies in the Wiki which look at substitution patterns between different creative products and business models (e.g. Sandulli and Martin-Barbero (2007), Calzada and Gil (2016), Cameron (1988)). These may be useful, but not conclusive, indications for the relevant market in a competition law case.

This is not the only way in which analyses in the distinct fields may inspire each other. Empirical studies on copyright seem to grapple with measurement challenges which are similar to those of competition law scholarship and practice: how product quality, creativity, and innovation is to be defined and measured. Studies assessing the increases in ‘quality’ of products or in ‘creativity’ or ‘innovation’ in creative industries (e.g. Waldfogel (2017), EY (2014)) may provide food for thought for competition law too.

This becomes increasingly important, as competition law broadens its focus from (merely) static efficiency to dynamic efficiency. This focus on static efficiency is not just visible in older competition law scholarship, but also in copyright scholarship which refers to competition (law). Handke and Towse (2007)’s study found that Copyright Collecting Societies remain an efficient way of distributing remittances for copyright to artists: although they tend to act as monopolies, their pricing is still close to market point. Handke and Towse’s 2007 study put forward that Digital Rights Management may take over some of the functions of collecting agencies in the future, as well as the possibility that new organisations would enter the market for license fee collecting but that this increased competition would be unlikely to result to fairer pricing. Such conclusions are interesting, since in a traditional price-centric interpretation of competition law, these conclusions may indicate that there are no concerns for competition law. However, in a more dynamic interpretation of competition law, such as that advocated in recent years, innovation and product diversity may be at least as important as prices.

Future directions of research

Competition law may come in, to remedy distortions of competition in copyright-related markets. The review of the Wiki shows that some studies indeed see competition law as a solution of last resort. At the same time, we should be mindful that competition law is not a panacea for all the apparent excesses of copyright: where market power increases without anti-competitive conduct, competition law is unlikely to apply. In those cases, a change in copyright law may be more suited than the application of competition law. To identify those scenarios, future research could look into the effects of copyright on competition and welfare, against the background of the possibilities and limits of competition law.

Future research could also ask whether the goals of copyright and competition law actually align in the long run, particularly as current policy and activism moves towards a combination of competition and copyright principles. Do exclusive rights, and the individual incentives they generate, always lead to the desired supply of creative products? The work found in the Wiki presents a really interesting start to answering this question. However, the findings in the Wiki on the effects on welfare of exclusive rights, on the one hand, and unauthorised copying, on the other, are not conclusive. More research is needed, particularly at the level of specific industries, into the benefits of exclusive rights versus open competitive markets. This research could look at the question by considering both copyright law (and its exceptions) and the principles of competition law. This is unlikely to ever be a completed project: as technology and business models change in a particular industry, so might the best approach.

Another future avenue for research comes with the reinvigorated concern for dynamic efficiency in competition law. Where copyright and competition law use similar concepts (‘quality’, ‘innovation’) which they attempt to measure, scholars of the two disciplines may wish to cooperate. They could research whether we can agree on a common vocabulary and understanding, and whether similar indicators could be developed to measure quality and innovation in copyright and competition law studies.

Last but not least, digital platforms have been a topic of concern to both copyright and competition law. Quite a few studies in the Wiki analyse the effects of digital platforms and business models on creative markets. In recent years, regulators have seemed keen to tackle the power and conduct of platforms through a blend of competition law and IP law principles. If this trend is set to continue, the importance of competition law for copyright, and vice versa, will only increase. Empirical studies assessing the implications of platform (regulation) would do well to consider both angles. As digital markets gain in further prominence, so does the need to consider copyright and competition law alongside each other.

Remember to register by Wednesday 13 October to join us at the 21 for 21 Copyright Evidence: Synthesis and Futures conference!

List of additional sources (beyond core scope of the Copyright Evidence Portal)

Abbe Brown, Smita Kheria, Jane Cornwell, and Marta Iljadica (2019) Contemporary Intellectual Property: Law and Policy (OUP, 5th edn)

Magali Eben (2021) The antitrust market does not exist: pursuit of objectivity in a purposive process. Journal of Competition Law and Economics, 17(3), pp. 586-619