This post is part of a series of evidence summaries for the 21 for 2021 project, a CREATe project within the AHRC Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC). The 21 for 2021 project offers a synthesis of empirical evidence catalogued on the Copyright Evidence Portal, answering 21 topical copyright questions for the 21st century. In this post, Leonhard Dobusch (Professor of Business Administration at the University of Innsbruck) and Konstantin Hondros (Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Institute of Sociology at the University of Duisburg-Essen) synthesise the empirical evidence relating to copyright and the concept of openness.

This post is part of a series of evidence summaries for the 21 for 2021 project, a CREATe project within the AHRC Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC). The 21 for 2021 project offers a synthesis of empirical evidence catalogued on the Copyright Evidence Portal, answering 21 topical copyright questions for the 21st century. In this post, Leonhard Dobusch (Professor of Business Administration at the University of Innsbruck) and Konstantin Hondros (Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Institute of Sociology at the University of Duisburg-Essen) synthesise the empirical evidence relating to copyright and the concept of openness.

Introduction

“Openness” is a concept of exceptional breadth and is adopted in multifaceted ways and various contexts, both academically and by practitioners. Openness refers to practices of handling knowledge and to a certain willingness to involve new strands of actors. Whether these practices are actually new, as they are often enabled or fostered by promises of novel information and communication technologies (ICTs), or rather represent “old wine in new bottles” (Trott & Hartmann, 2009), there is no doubt that we can observe a “second coming of openness within the supposedly already-open society” (Tkacz, 2012: 400) over the past couple decades.

In this blog, we will focus on domains such as Open Source Software, Open Access, Open Education, Open Government, Open Science or Open Content more broadly that explicitly follow a normative program of openness. All these approaches can be classified as programmatic because they share (1) an affirmative stance towards openness from an ethical, political and/or an economic perspective and because (2) the underlying goal of most research in these fields is to identify efficient ways or degrees of openness (Dobusch & Dobusch, 2019).

Within these domains, we suggest to further distinguish mere metaphorical and material approaches to openness. In the case of the former, certain practices are described and differentiated from previous practices by applying the label of openness but no formal codification or regulation of openness is happening. Laursen and Salter (2006: 146), for example, classify firms as open “who are more open to external sources or search channels are more likely to have a higher level of innovative performance.” While we do not doubt that metaphorical approaches to openness might be highly consequential for organisational and management conduct, we are focusing on more material approaches to openness that are characterized by explicitly and formally opening certain forms of knowledge to new, previously excluded, groups of actors.

A common denominator of such material approaches to openness is a certain departure from classical business models based on (the exploitation of) exclusive intellectual property rights (IPRs). Examples include the use of standardized forms of open licensing (e.g., Open Source Software licences or Creative Commons licences) or sharing knowledge in order to prevent others from acquiring exclusive IPR (e.g., property-preempting investments; Merges, 2004).

In this blog, focusing on copyright-related aspects of open approaches across domains, we will first develop a typology of openness in organising copyright, ranging from permissive over viral to restrictive openness. Based upon this typology, we will review the empirical evidence available for each of these three types of organising copyright-related openness. We conclude with some reflections on potential avenues for future research within and across the various domains of openness.

Note: Whilst we focus on empirical evidence relating to openness and copyright, we will draw parallels from studies on IP conceived broadly, or studies on other forms of IPRs (e.g., patents), where literature on openness is more conspicuous.

A Basic Typology of Openness in Organising Copyright

While there is already ample literature on various approaches to limit the scope of IPR protection (e.g., Hall, 2016; Hope, 2009; Weber 2004) most works focus on one specific domain (e.g., software, educational material) or at least one specific form of IP (e.g., copyright, patent law). Furthermore, Sinnreich et al. (2021) recently suggested a historical typology, distinguishing the periods of utopian, creative, and utilitarian openness. The following typology is an attempt to complement these findings and generalize beyond domains and forms of IP.

a) Permissive Openness

Permissive approaches to openness mostly seek to mimic the (lack of) copyright protection associated with knowledge that is in the public domain. Consequently, permissive approaches place only very little restrictions beyond attribution requirements on third parties use of said knowledge (Erickson et al., 2015). Importantly, permissive openness allows others to even use and integrate knowledge in more restrictively regulated contexts. Examples include open source software licences such as Apache, MIT or BSD and Creative Commons Zero in the realm of copyright and property-pre-emptive investments that publish knowledge with the sole aim to prevent others from patenting it.

In addition to a growing percentage of open source software code that is released under permissive licences (Hofmann et al., 2013), we find permissive openness to be the preferred approach in domains such as Open Access, Open Science and Open Data. In all these domains key institutions and declarations recommend the use of permissive licences such as CC0 or CC-BY. However, we find permissive approaches also in the context of some offerings of royalty-free music or online picture services (e.g., Unsplash, Pixelio).

b) Viral Openness

Viral approaches to openness seek to preserve the same kind of openness in any derivative works that use or incorporate knowledge published under a certain open copyright regulation, thereby prohibiting re-proprietization (Klimpel, 2013). The most prominent examples are open source software licences that include a “copyleft” clause such as the GPL used for the GNU/Linux operating system. Wikipedia and its sister projects such as Wiktionary or Wikibooks also use a viral approach for their content, applying the CC-SA licence as standard.

Given the relevance in terms of use contexts and reach, the viral approach by GNU/Linux and Wikipedia alone justifies distinguishing their viral approach as a separate type of openness in organising copyright. As a consequence, viral openness can be found in any domain where either GNU/Linux or Wikimedia (the organisation behind Wikipedia and its sister projects) content is being (re-)used such as, for example, Open Educational Resources (e.g., Petrides et al., 2008).

c) Restrictive Openness

Restrictive approaches to openness only selectively depart from traditional forms of copyright protection, waiving copyright restrictions only for specific use cases or fields. One of the most prominent examples for such an approach is the use of Creative Commons licences that include the “non-commercial” module, preserving most forms of commercial exploitation to the licensor (Dobusch & Kapeller, 2012). In addition, many non-standardized forms of opening access to IP-protected knowledge fall into this category. To give an example from the realm of patent law, the Medicine Patent Pool (MPP) offers access to patented knowledge covered by its agreements only to certain world regions and, depending on the agreement, certain areas of application (Cox, 2012).

Existing evidence and research agendas

We structure the overview of existing empirical evidence based on the three ways of handling openness, starting with evidence about permissive openness. We present evidence across qualitative and quantitative methodologies, as well as diverse empirical fields of study from the creative economy, ICT, or bio-technology.

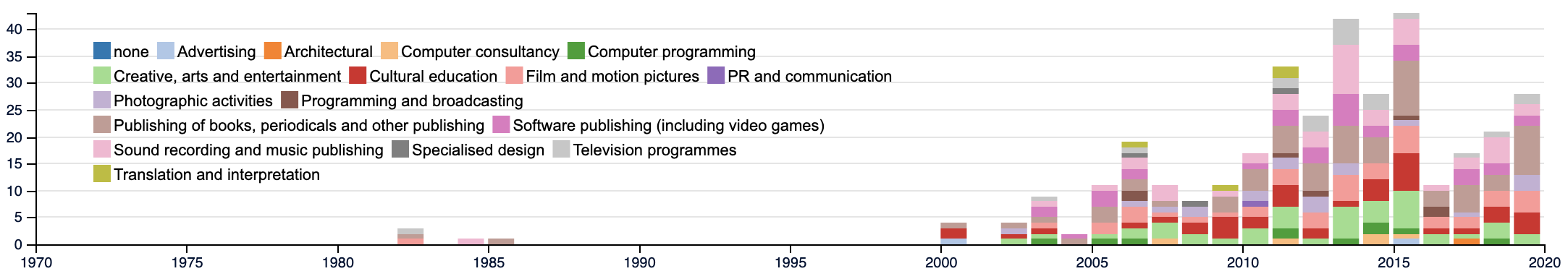

Figure 1: Timeline generated on Evidence Viz – studies differentiated by industry relating to keyword ‘access’

a) Permissive Openness

Most of the literature with evidence for permissive openness is situated in the ICT sector and connected to software development. In the creative economy, studies investigate the public domain, netlabels, but also open licensing practices of copyrighted works. We start with evidence about the public-domain-like approaches as the most radical form of permissive openness.

There is evidence, on the one hand, about implementing a public domain approach, particularly in the field of scientific knowledge production by adopting open access publishing practices. Salter and Martin (2001) summarize in a seminal review article empirical econometric studies, surveys, and case studies about publicly funded basic research. The authors suggest “substantial” economic benefits mainly from “spillovers and the existence of localisation effects,” like “increasing the stock of useful knowledge,” or the “training of skilled graduates,” and thus take a broad perspective on potential benefits. The authors attempt to measure the social rate of return to investments in basic research, which are benefits generated for the whole of society, and can distinguish between fields of knowledge where publicly funded basic research matters greatly, particularly material sciences and computer sciences. They argue that traditional “market failure” arguments and justifications for restrictive copyright practice fall short and do not account for the potential of publicly available knowledge and thus underscore the relevance of a public domain approach to openness. These results are echoed in studies looking at citation advantages of open access published research and the impact generated by open access (see e.g., Antelman, 2004; Arendt, Peacemaker, & Miller, 2019). Furthermore, Kuchma (2011) quantitively studies open access journals in developing and transitioning countries (n=556) and evidences the widespread adoption (94%) of particularly permissive licensing terms across open access journals.

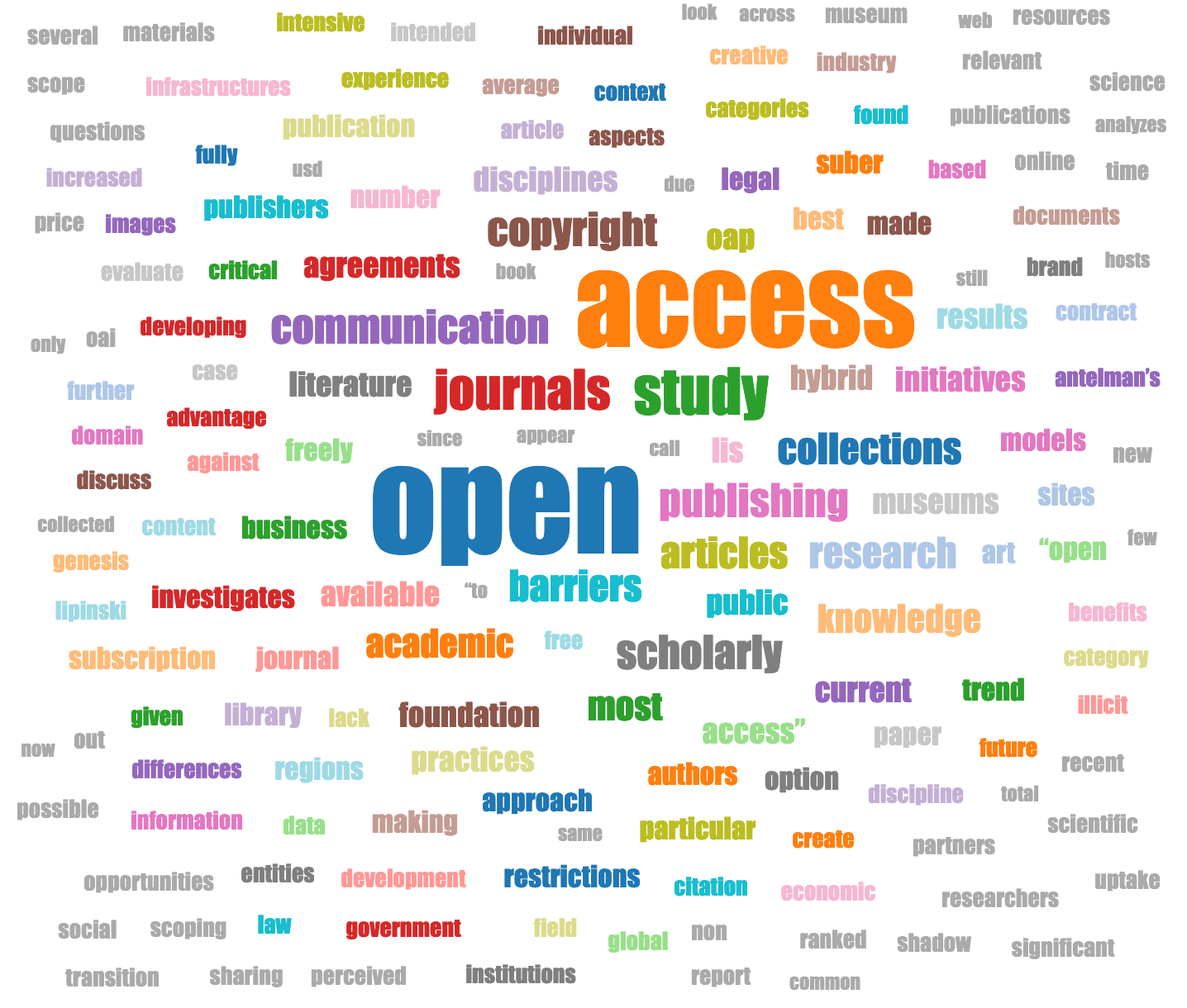

Figure 2: Word cloud generated on Evidence Viz – response to keyword search ‘open access’ (showing associated keywords journals, scholarly, research, academic)

On the other hand, evidence from the creative economy shows how radically permissive openness feeds back into organisational processes via “spillovers.” Extant studies of the economic specificities of the public domain question its value for the creative industries (Erickson et al. 2015) and whether firms can “thrive without copyright” (Erickson 2018), when they solely build their activity around non-protectable input from the public domain instead of creating copyright-protected content. In a study based on Interviews (22) with managers of firms in the creative industry incorporating public domain input, Erickson (2018: 1) finds “improvements and a reduction in transaction costs related to seeking and obtaining permission to innovate existing ideas,” which is echoed in the following quote of one manager:

“When you find something in the public domain, at the time of your discovery it is less known as a public domain item. You use it creatively so that it becomes known. That’s fine because you’ve moved on by the point when everyone is catching up with you. (MyVox Songs)” (see Erickson, 2018: 8)

With respect to other, a little less but still permissive approaches, Hofmann et al. (2013) conducted a study about open source licence choice in open source projects. They analyse a database “snapshop” taken from Ohloh.net, a community platform that indexes the open-source software development community. The evidence from their quantitative data (more than 5000 individual cases) that covers about 15 years of open source projects (from the early 1990s until 2008) suggests that open source projects increasingly choose permissive licences over restrictive ones. They established a “changing point” for this development in 2000/2001 and argue that this change comes with a “growth of commercially sponsored open source communities” (Hofmann et al., 2013: 255), indicating an economic benefit of permissive openness when compared to viral approaches.

For the creative economy, we have evidence about how Creative Commons licensing gave rise to netlabels as an alternative model of music distribution, building on online spaces only and (usually) sidestepping typical commercial constraints of the music business (Galuszka, 2012). However, only rarely do studies look at the influence of permissive licensing practices on creation processes in the creative economy. Miszczyński (2021) investigates licensing and production practices in the “sound industry”, with a focus on the implementation and usage of permissive CC-licences. Following a qualitative and variance-based methodology and building on interviews with 17 “European creators” the study carves out the potential of these licences to “free creativity from constraints imposed by copyright intermediaries” (Miszczyński, 2021: 357). A musician from Poland underscores the relationship between permissiveness and creativity:

“you don’t have to ask, you don’t have to think, you just take it and put it in your track—everybody already agreed you can do it.” (Miszczyński, 2021: 359)

Since permissive openness offers a wide range of potential angles on how to contractually define usage-boundaries for copyright, including the option to re-license content under different terms, permissive approaches to openness potentially overlap with more restrictive forms of knowledge sharing.

b) Viral Openness

Viral openness shares similarities with permissive openness such as a generalised way of granting rights that include the right to commercial exploitation, yet the intention or justification for openness differs significantly. While permissive openness mainly strives to foster dissemination and further creation, viral openness seeks to also secure openness of derivative creations, thereby creating an ever-growing commons of openly available materials.

An important resource of viral openness evidence is Bollier’s (2009) book “Viral spiral” that offers insights about the viral effects of Creative Commons licences from cultural to scientific fields. Though, rather in the form of anecdotal evidence, the author for instance reports about a Spanish short film that went viral, not least stimulated by a CC BY-NC-SA licence that allowed “viewers not only to share the film, but to remix for noncommercial purposes so long as they use the same licence. (ibid: 141).

In an interview-based study in the music industry (24 interviews with musicians and business experts), Schwetter (2015) offers evidence of how musicians integrate different Creative Commons licences in their practice. A common thread among the interviewed musicians revolves around a gradual development from using only the most restrictive licences (CC-BY-NC-ND) to less restrictive ones (CC-BY-SA). One musician summarises their experience with using too restrictive licences:

“The Creative Commons NonCommercial license, for example, is completely useless in my opinion. I had used [them] myself, but at some point I realized that it was total nonsense for me in the end. Because using them ultimately means that it is not played at parties (…).” (Schwetter, 2015: 239, translation Konstantin Hondros)

The musician argues that for their purposes, a licence that precludes commercial use is not useful, because parties with DJs are commercial events. Finding enough people listening to their music, and eventually going viral with one of their tracks requires, in turn, the right kind of openness. More generally, these findings echo evidence from the realm of permissive openness on a gradual change from more to less restrictive licensing. In a similar vein, interesting evidence from the film industry suggests that filmmakers strategically choose licences to support viral openness for specific media only. In a study about open-content filmmaking, Campagnolo et al. (2018) find that open content filmmakers use “Creative Commons for digital works, and all-rights-reserved for televisual works,” indicating a strategic choice towards the viral potential of online dissemination.

In the ICT sector, Andersen et al. (2012) differentiate between proprietary- (patents & copyrights) and non-proprietory (open-source) IP. Building on “confidential micro data” of 38 UK-based firms in ICT they find that in cases of inter-firm IP exchange, using an open source strategy was successful, particularly with regard to innovation benefits as well as to build relationships with industry networks, both underscoring a viral effect of openness in knowledge sharing.

c) Restrictive Openness

Creative Commons licences that prohibit commercial usage are among the most prominent examples for restrictive openness as outlined above. Interestingly, regulatory uncertainty associated with the Creative Commons Non-Commercial restriction, about what effectively counts as a non-commercial context and what does not, hampers its adoption. In a study analysing quantitative survey data provided by Creative Commons itself, Dobusch and Kapeller (2012) find that it is the rule’s inherent ambiguity that actually contributes to its dissemination as long as different interpretations of the rule are compatible to each other.

Restrictive openness is even more common in less standardised approaches than Creative Commons. In a study applying netnographic techniques to qualitatively map platforms dedicated to the commercial exchange of music samples and sample libraries, Hondros (2020) finds that it is actually platform terms that matter most for what is or what is not permitted regarding the usage of a purchased sample/sample library. There is a wide variety of levels of permissiveness/restrictiveness ranging from using samples un-altered to the demand that purchased samples need to be interpreted as inspiration only, which makes strong alteration of a sample necessary when it is used in a novel song.

In addition to examples for restrictive openness in the creative economy, open innovation contexts such as bio-technology – a sector usually heavily protected by different forms of IP – adopt more restrictive approaches. For instance, Hagedorn and Zobel (2015), in a mixed-method study based on interviews and a survey, find:

“[a] preference for the governance of their OI relationships with other firms through formal contracts. Also, despite the open nature of OI, firms still see IPR as highly relevant to the protection of their innovative capabilities”

This is echoed by Grimaldi et al. (2021: 156) who quantitatively investigate IP strategies of 158 Italian firms partaking in forms of open innovation and find a proliferation of an “impromptu” strategy, “which describes firms protecting their IP without a clear purpose.” Also, in a single, longitudinal case study of a bio-pharmaceutical company and their open innovation strategies, Toma, Secundo and Passiante (2018: 501) show:

“[a] mix of formal and informal tools for IP protection are used, with a final attempt to maintain control over different technological solutions during their validation process and profiting from stable R&D collaborations with research partners.”

An intriguing finding across investigations of open innovation companies is the multiplicity of strategies ranging from more restrictive to less restrictive adoptions of openness applied simultaneously. In a study about licence choice in open 3D printing, Jee and Sohn (2018) find that creators choose rather permissive or restrictive licences along the differentiation of functional (rather NC licences) and aesthetic (rather non-NC licences) content. However, a lot of content is both functional and aesthetic, with no significant difference in terms of licence choice. The authors argue that these findings point to a potential deficiency of current licences and suggest to develop new licences that cover both the functional and aesthetic aspects of 3D printing content.

This evidence from the field of open innovation in knowledge-intensive industries leads back to our overall argument and framework that basically claims that openness is a multifaceted practice that rather relies on grey areas between copyright-permissiveness or copyright-closure instead of a final decision for either one of these two.

Future directions for research

Taken together, the evidence on different kinds of openness suggests at least three important lines of discussion.

First, there seems to be a (historic) trend towards applying increasingly permissive openness in different fields, particularly in software development and the creative economy. However, regarding software, the available data is a bit outdated given the rapid turnovers in this sector. Also, for the creative economy and particularly the music industry, this trend should be looked into more carefully. The ongoing transformation towards streaming in some ways mirrors characteristics of openness for consumers, while keeping complete copyright constraints for producers (or prosumers). The influence of this transformation on open licensing approaches is still very much unclear.

Second, the evidence suggests that rather patent-based environments (open science, open innovation) tend to combine permissive with restrictive knowledge-sharing strategies. While this shows how particularly IP-protected economic sectors increasingly apply forms of openness, it is still unclear whether we will observe a trend towards increasing permissiveness in these sectors, as well.

Third, though we have analytically categorised exemplary evidence of openness and copyright into three types of openness, we find overlaps between rather permissive and rather restrictive practices in many creative processes with open approaches towards copyright. Though we believe our analytical differentiation is useful for a broad understanding of various approaches to openness and copyright, the boundaries drawn are much more porous in empirical cases. Furthermore, forms of open licensing like royalty-free licences can vary heavily, ranging from permissive licensing agreements to restrictive ones.

With respect to directions for future research, we see the need for a more systematic assessment of the (inter-)organisational arrangements around the three different types of openness in organising IP. For example, whether and how approaches to openness that are more permissive in terms of IP require additional organisational efforts in terms of partner and community management.

Concerning the relative growth of permissive forms of openness observed across domains, we still lack explanations for why and how this shift happens (see also Sinnreich et al., 2021). Also, we know little about the consequences of a shift towards more permissive openness for creative practices. Here, for example, comparative case studies of organisations switching to more permissive approaches to openness could provide valuable insights.

Finally, we are only beginning to see evidence on how digital platforms in the creative economy promote or inhibit openness, and whether and how they are or could become “intermediaries of openness.” In other words, not just organisations pursuing open approaches, but also complementary infrastructures of openness should be included in research on openness of organising copyright.

List of additional sources (beyond core scope of the Copyright Evidence Portal)

Andersen, B., Rosli, A., Rossi, F., and Yangsap, W.. 2012. “Intellectual property (IP) governance in ICT firms: strategic value seeking through proprietary and non-proprietary IP transactions.” International Journal of Intellectual Property Management 5 (1), 19-38.

Bollier, D. (2009). Viral spiral: how the commoners built a digital republic of their own. New York: New Press.

Cox, K. L. (2012). The medicines patent pool: promoting access and innovation for life-saving medicines through voluntary licenses. Hastings Science & Technology Law Journal, 4, 291-324.

Dobusch, L., & Dobusch, L. (2019). The Relation between Openness and Closure in Open Strategy: Programmatic and Constitutive Approaches to Openness. In: Seidl, D., von Krogh, G. & Whittington, R. (Eds.): The Cambridge Handbook of Open Strategy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 326-336.

Dobusch, L., & Kapeller, J. (2012). Regulatorische Unsicherheit und private Standardisierung: Koordination durch Ambiguität. In: Conrad, P. & Koch, J. (Eds.): Steuerung durch Regeln. Gabler, Wiesbaden, 33-81.

Galuszka, P. (2012). The rise of the nonprofit popular music sector–the case of netlabels. In: Karja, A.-V., Marshall, L., & Brusila, J. (Eds.): Music, Business and Law. Essays on Contemporary Trends in the Music Industry. Helsinki: IASPM Norden & Turku: International Institute for Popular Culture, 65-90.

Grimaldi, M., Greco, M., & Cricelli, L. (2021). A framework of intellectual property protection strategies and open innovation. Journal of Business Research, 123, 156-164.

Hagedoorn, J., & Zobel, A.-K. (2015). The role of contracts and intellectual property rights in open innovation. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 27(9), 1050-1067.

Hall, A. J. (2016). Open-source licensing and business models: Making money by giving it away. Santa Clara Computer & High Technology Law Journal, 33, 427-437.

Hofmann, G., Riehle, D., Kolassa, C., & Mauerer, W. (2013). A dual model of open source license growth. In: IFIP International Conference on Open Source Systems (pp. 245-256). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Hope, J. (2009). Biobazaar: the open source revolution and biotechnology. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hondros, K. (2020). Onlinemärkte für Musiksamples und die Fixierung flüchtiger Waren. In: Schrör, S., Fischer, G., Beaucamp, S., & Hondros, K. (Eds.): Tipping Points. Interdisziplinäre Zugänge zu neuen Fragen des Urheberrechts des Urheberrechts. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 155-174.

Klimpel, P. (2013). Free Knowledge based on Creative Commons licenses. Wikimedia Deutschland.

Laursen, K., & Salter, A. (2006). Open for innovation: the role of openness in explaining innovation performance among UK manufacturing firms. Strategic Management Journal, 27(2), 131-150.

Merges, R. P. (2004). A new dynamism in the public domain. The University of Chicago law review, 183-203.

Miszczyński, M. (2021). Creative Commons Licensing and Relations of Production in the Sound Industry. Polish Sociological Review, 215(3), 353-368.

Petrides, L., Nguyen, L., Jimes, C., & Karaglani, A. (2008). Open educational resources: inquiring into author use and reuse. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning, 1(1-2), 98-117.

Salter, A. J., & Martin, B. R. (2001). The economic benefits of publicly funded basic research: a critical review. Research Policy, 30(3), 509-532.

Schwetter, H. 2015. Teilen–und dann?: Kostenlose Musikdistribution, Selbstmanagement und Urheberrecht. kassel university press GmbH.

Tkacz, N. (2012). From open source to open government: A critique of open politics. ephemera, 12(4), 386.

Toma, A., Secundo, G., & Passiante, G. (2018). Open innovation and intellectual property strategies. Business Process Management Journal, 24(2), 501-516.

Trott, P., & Hartmann, D. A. P. (2009). Why ‘open innovation’ is old wine in new bottles. International Journal of Innovation Management, 13(04), 715-736.

Weber, S. (2004). The success of open source. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.