CREATe presents new research: “The emergence of platform regulation in the UK: an empirical-legal study” by Martin Kretschmer, Ula Furgał and Philip Schlesinger. This paper draws on CREATe’s current work on platform regulation within the AHRC Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre (PEC) and provides an empirical mapping of the UK’s regulatory landscape with an assessment of risks and opportunities for the UK creative industries. The research is published simultaneously as a PEC Discussion Paper and Policy Report.

Professor Martin Kretschmer, Professor of Intellectual Property Law and Director of CREATe said:

“Fake news, cyber attacks, predatory acquisitions. Dangerous things are happening on online platforms. But how do we, as a society, make decisions about undesirable activities and content? UK policy makers hope to delegate tough choices to the platforms themselves, focussing on codes of practice and codes of conduct supervised by regulatory agencies, such as Ofcom (for a new ‘online duty of care’) and competition regulator CMA (through a ‘digital markets unit’). Our new empirical study shows how this approach emerged, and how it compares in a global setting.”

This high profile research conducted as part of the AHRC Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre (PEC) signals concern that the evolving regulatory structure appears to be blind to the effects of platforms on cultural production and diversity. The role of ranking and recommendation algorithms as cultural gatekeepers still needs to be integrated into the platform policy agenda.

Professor Philip Schlesinger, Professor in Cultural Theory (Centre for Cultural Policy Research and CREATe), said:

“Platform regulation is now at the heart of how democracies conduct themselves. It’s also increasingly at the heart of how we manage rules for our digital social connectedness. So understanding how regulation works and the forces that are shaping it have become crucial for everyone. It’s important that the present rush to regulate doesn’t ignore the huge contribution of creative industries to the cultural economy. And since the UK’s multinational diversity has been thrown increasingly into relief by Brexit and the pandemic, how regulatory policy plays out will be of special interest to the devolved administrations.”

Introduction

Platforms are increasingly seen by governments and policymakers as distinct new regulatory objects that need to be addressed. The UK’s regulatory options have begun to be more clearly defined with new powers vested in the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) and also the Office of Communications (Ofcom).

How regulation plays out in a national context needs to be seen in the wider context of international developments – such as the EU Digital Services and Digital Markets Acts, antitrust moves in the USA and the Australian stand-off between state and platforms over payment for news content. The emergence of the new regulatory object of ‘online platforms’ is part of a global trend, reflecting a fundamental reassessment of tech power and state sovereignty.

The UK has a profusion of bodies that in various ways relate to how the internet is, or may be, regulated. We show that the key policy decision was to focus, separately, on ‘Online Harms’ (through Ofcom) and Competition (through the CMA and a new Digital Markets Unit). This extends the two bodies’ jurisdictions but also creates added complexity and a need to coordinate distinct functions.

We demonstrate how the debate over the regulatory landscape in the UK became shaped as a response to perceived social and economic harms caused by the activities of US multinationals. Two companies, Google and Facebook, account for three quarters of all references to firms in our sample of eight official reports. Only two platforms headquartered in Europe are mentioned, while absolutely no UK firms feature. This points to a structural problem in how the field is constructed, focusing on sovereignty. Regulatory developments may not be geared to support innovation.

We identify codes of practice or conduct as a preferred way of mediating between regulators and the regulated and the centrality of the mix of formal and informal regulatory cultures at play in the UK.

We emphasise the importance of the gatekeeper concept, and of transparency and ‘due process’ in order to understand regulatory implications of algorithmic approaches (such as recommender systems and content filtering) for the creative industries.

Lastly, we explore the outlook for the UK as a regulatory convening power. Are there distinctive advantages in the negotiation of global regulatory competition deriving from the UK’s multi-agency approach? How influential will be the regulatory structure the UK is developing for the regulation of online platforms?

This working paper presents the findings of a first comprehensive mapping of a rapidly evolving regulatory field.

Scope of the study

The PEC research reported here offers a novel empirical perspective. We conducted a socio-legal structural analysis using a primary dataset of eight official reports issued by the UK government, parliamentary committees and regulatory agencies during an 18-month period (September 2018 to February 2020).

The period captures the main response to the UK government’s commitment to legislate to address a range of problems that originate online. Selected primary sources for analysis include two Government-commissioned independent reports (Cairncross, Furman), a White Paper (Online harms), two parliamentary reports (DCMS Committee House of Commons, Communications Committee House of Lords), and three agency reports (Competition and Markets Authority, Ofcom, Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation).

Through a legal content analysis of these official documents,

- We identify over 80 distinct online harms to which regulation has been asked to respond;

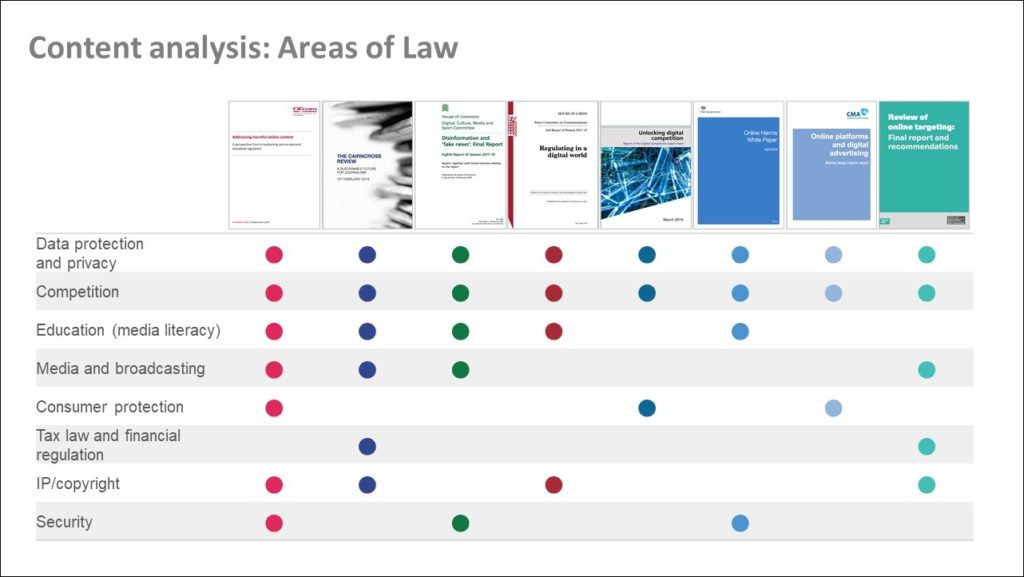

- We identify eight subject-areas of law referred to in the reports (data protection and privacy, competition, education, media and broadcasting, consumer protection, tax law and financial regulation, intellectual property law, security law);

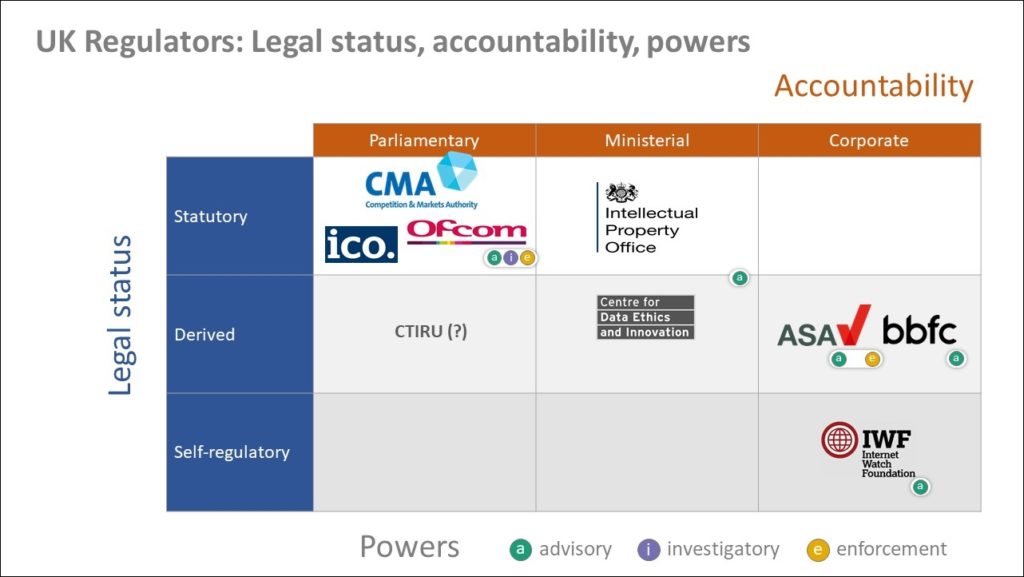

- We code nine agencies mentioned in the reports for their statutory and accountability status in law, and identify their centrality in how the regulatory network is conceived in official discourse (Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), Competition and Market Authority (CMA), Ofcom, Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), Intellectual Property Office (IPO), Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDAI), Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU));

- We assess their current regulatory powers (advisory, investigatory, enforcement) and identify the regulatory tools ascribed in the reports to these agencies, and potentially imposed by agencies on their objects (such as ‘transparency obligations’, ‘manager liability’, ‘duty of care’, ‘codes of practice’, ‘codes of conduct’, ‘complaint procedures’);

- We quantify the number of mentions of platform companies in the reports, and offer an interpretation of the emerging regulatory field.

Key findings

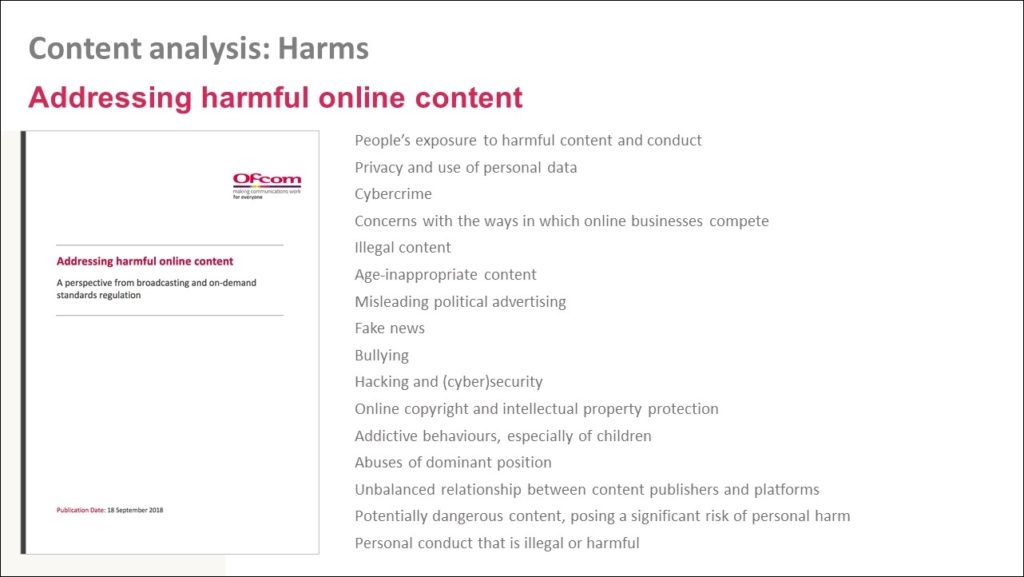

1. Much of the regulatory discussion in the UK has focused on harms, with agencies positioning for regulatory jurisdiction and new powers. Child protection, security and misinformation concerns surface in many different forms. We also identify a deep disquiet with lawful but socially undesirable activities. The following figure presents the result of a content analysis of harms mentioned in one of the eight sample reports, Ofcom’s discussion paper Addressing harmful online content of September 2019, which can be understood as the opening gambit by a regulatory agency responding to the UK government’s intention to legislate.

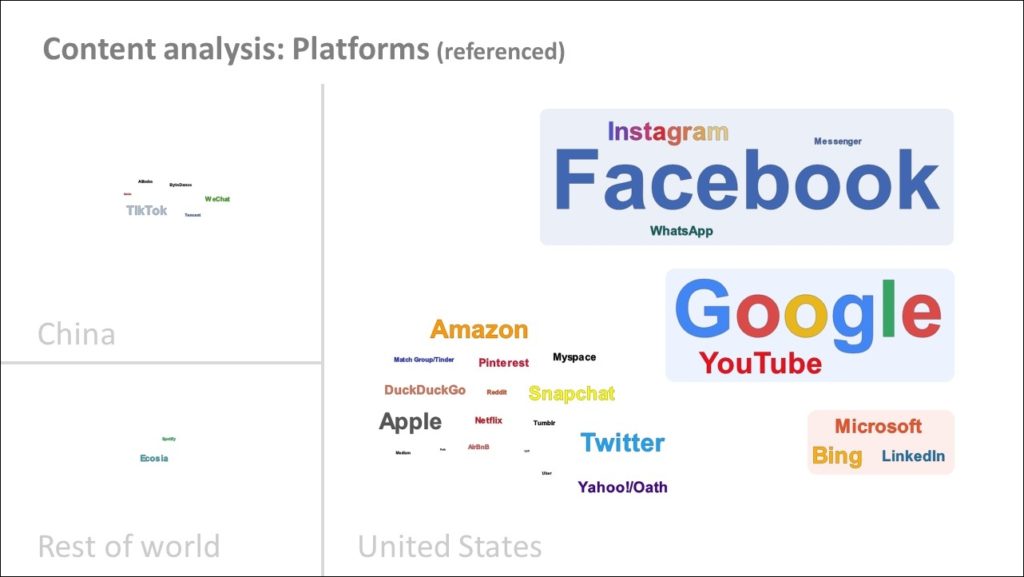

2. The next figure offers a word-cloud representation, with firms mentioned in the eight sample reports tagged by their national headquarters. 3320 (76%) of 4325 references made are to two US firms and their subsidiaries: Google (including YouTube) accounts for 1585 references; Facebook (including Instagram, WhatsApp and Messenger) accounts for 1735 references. Only two platforms headquartered in Europe are mentioned (Spotify and Ecosia). Chinese firms are referenced 61 times. Not a single UK-headquartered firm figures.

3. What are the legal levers that may be used to implement solutions to the harms identified? The following figure codes the subject areas of law mentioned in each of the eight sample reports. The areas of law can be distinguished by their underlying rationales, be they economic, social, or fundamental rights based. Are the underlying principles commensurable? It is evident that data and competition solutions have been foregrounded in all eight reports. The consumer law perspective is comparatively weak, as are interventions through the fiscal system. Security interventions lack explicit articulation.

4. The nine most prominent agencies mentioned in the sample reports are (in alphabetical order): Advertising Standards Authority (ASA), British Board of Film Classification (BBFC), Competition and Market Authority (CMA), Ofcom, Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), Intellectual Property Office (IPO), Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation (CDAI), Internet Watch Foundation (IWF), Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU). The following figure codes their legal status, accountability and current regulatory powers (advisory, investigatory, enforcement).

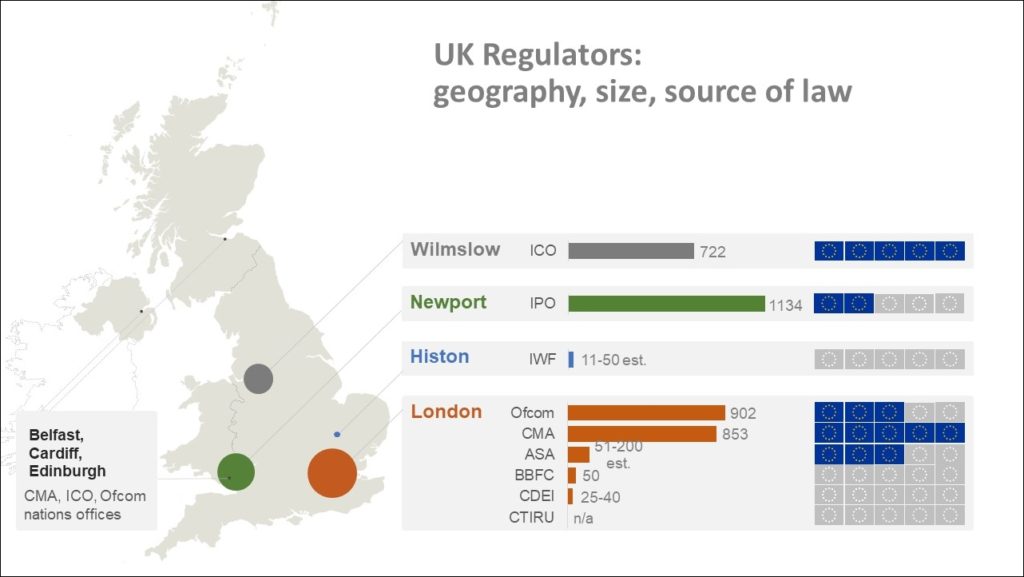

5. Looking at the geographical profile and labour force of these nine agencies, it is evident that regulatory power is London-centric, with a minor presence in the UK’s devolved nations (Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland). Few public details about the Counter-Terrorism Internet Referral Unit (CTIRU) are available. In total, fewer than 3000 staff are employed in those regulatory agencies that we have identified as broadly relating to platforms. For comparative context, we note that Facebook employs about 35,000 human content moderators (who are mostly outsourced). The resources required to install a functioning governance system for platform activities at scale will be considerable.

Conclusions and recommendations

- The detailed empirical analysis shows that the UK’s regulatory activism initially came to a head in 2019, and then led to key regulatory decisions about new legislation and regulatory competences late in 2020. This involved the establishment of a Digital Markets Unit under the aegis of competition regulator CMA, and the identification of communications regulator Ofcom as regulator of a new online ‘duty of care’

- The development of distinct new regulatory powers relating to content, data and structure is clearly visible, reflected in the network centrality of several agencies, Ofcom, CMA, and to a lesser extent the Information Commissioner. Intermediary liability (for content), competition law and data protection have different rationales. The UK’s evolving approach points to coordination between multiple agencies, rather than formalising a hierarchy with a ‘super-regulator’ at the apex. Agency self-organisation, for example through a new Digital Regulation Cooperation Forum (DRCF), will be an important locus for shaping and implementing regulatory reality on the ground

- The sampled discourse shows that there has been very little public reflection on regulatory processes. For example, how to

- monitor (information gathering powers),

- trigger intervention,

- prevent and remove content (filtering technologies, notifications process, redress),

- assess compliance (transparency).

- For the creative industries, it is a concern that the evolving regulatory structure appears to be blind to the effects of platforms on cultural production and diversity. Copyright law is responsible for most takedown actions but lacks oversight. The role of ranking and recommendation algorithms as gatekeepers, as well as the dependence of remuneration flows to primary creators on such functions still needs to be integrated into the platform policy agenda.

- An important regulatory characteristic of the UK appears to be the emphasis on codes of practice or codes of conduct as a flexible and responsive regulatory tool. At core, the idea is to hold platforms to their own rules (such as their terms of service). Delegating state powers to firms in this way can be problematic, and requires a fundamental assessment of the relationship between the state and private powers. The focus on online harms, rather than innovation opportunities, may have led to a lack of clarity about regulatory goals.

- The UK’s key regulatory agencies are well networked internationally, and are playing an important part in contributing to an emerging global paradigm of platform regulation. There is a potential convening opportunity for the UK’s agency-led approach.

CREATe Platform Regulation Resource is available here.

The AHRC PEC Policy Brief can be downloaded here.

The full paper can be downloaded here.