December 15th, 2020 will be remembered as a momentous day in the relationship between big tech and society. You may think this is because the UK government announced long awaited measures to regulate online harms – measures that fundamentally change how platforms will have to police illegal and harmful content. The Internet platforms’ liability shield, also known as ‘safe harbour’, is being lifted.

In truth, December 15th is more likely to be remembered for the publication by the European Commission of legislation that aims to do the same, and much more: the Digital Markets Act (defining online gatekeepers with special behavioural obligations, in particular relating to access to data by other business users), and The Digital Services Act (addressing the liability of all online intermediaries, and reforming takedown and recommender systems).

But let’s start with the UK government’s response to the Online Harms white paper, and (Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport) Oliver Dowden’s statement in the House of Commons.

The UK will introduce a new ‘duty of care’ that makes social media firms, search engines and a wide range of internet services (including “consumer cloud storage sites, video sharing platforms, online forums, dating services, online instant messaging services, peer-to-peer services, video games which enable interaction with other users online, and online marketplaces”) responsible for the content seen by their users. Content that is produced not by the platforms but by users themselves. Content that may be legal but harmful. Content that may be hosted abroad but accessible in the UK. Content that may be end-to-end encrypted.

Ofcom, the UK communications regulator, will acquire a range of new powers. In extremis, failure by companies in their duty of care to remove material, such as child sexual abuse, terrorist material or suicide-promoting content (which will be made a crime by separate legislation), may result in fines of up to 10% of a company’s annual global turnover (or £18 million, whichever is higher). In Facebook’s case, this could be 10% of $70bn, an eye watering $7bn (based on 2019 figures).

While this is the headline communicated by the Secretary of State, more important in practice will be a new regulatory process by which companies will be held to their own terms of service. These will turn into ‘codes of practice’ approved by the regulator Ofcom. This is a flexible mechanism that allows for rapid adjustment to technological or cultural changes, such as the emergence of micro video sharing services targeted at minors (TikTok). Codes of conduct can address ‘lawful harms’ quickly. Examples of the use of this regulatory approach are varied, and of various success and transparency. Compare for example the codes of conduct regulating supermarkets’ relationship with their suppliers with those setting out control over intellectual property rights in the relationship between public service broadcasters and independent TV producers. The process of delegating state powers to private companies will require close attention.

It is no coincidence that the UK government moved now with the Online Harms statement and with the earlier announcement on November 27th of a Digital Markets Unit to be established within the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). The UK’s new regulatory framework for the platform economy anticipates, or you may want to say, preempts EU legislation that has been trailed for some time.

“Today Britain is setting the global standard for safety online with the most comprehensive approach yet to online regulation,” said DCMS Secretary Oliver Dowden. “We are entering a new age of accountability for tech to protect children and vulnerable users, to restore trust in this industry, and to enshrine in law safeguards for free speech.” In their press conference of December 15th, announcing the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, Executive Vice-President of the European Commission Margrethe Vestager and Thierry Breton, Internal Market Commissioner claimed much the same for the EU’s legislation.

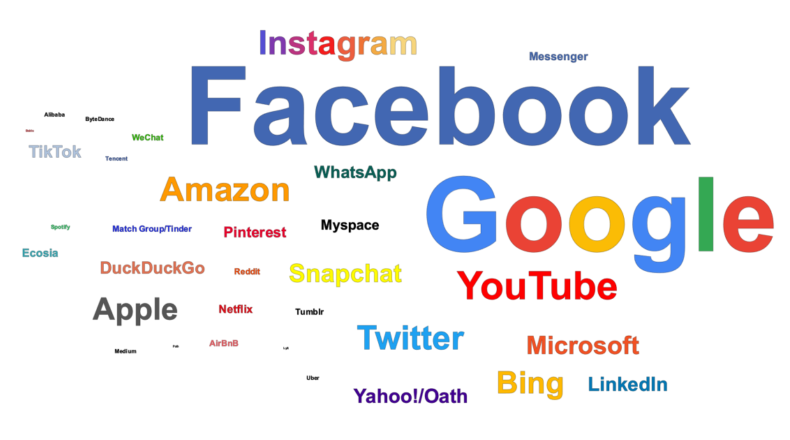

A common feature of both the EU’s and the UK’s approach is that legislators now single out a group of platform companies for special treatment, imposing ex-ante obligations, i.e. steps that need to be undertaken before any harm or breach in law has taken place. In the UK, the CMA’s Digital Markets Taskforce identifies these companies as firms with a Strategic Market Status (SMS): “This should be an evidence-based economic assessment as to whether a firm has substantial, entrenched market power in at least one digital activity, providing the firm with a strategic position (meaning the effects of its market power are likely to be particularly widespread and/or significant). It is focused on assessing the very factors which may give rise to harm, and which motivate the need for regulatory intervention.”

In EU terminology, the Digital Markets Act aims to target Gatekeepers. “These are platforms that have a significant impact on the internal market, serve as an important gateway for business users to reach their customers, and which enjoy, or will foreseeably enjoy, an entrenched and durable position. This can grant them the power to act as private rule-makers and to function as bottlenecks between businesses and consumers.”

The Digital Services Act defines Very Large Online Platforms (VLOP) that reach more than 10% of the EU’s population (45 million users), are considered systemic in nature, and are subject not only to specific obligations to assess and to control their own risks, but also to a new oversight structure. The Commission will acquire special powers in supervising such companies, including the ability to sanction them directly.

There will be graduated obligations such as:

- Rules for the removal of illegal goods, services or content online;

- Safeguards for users whose content has been erroneously deleted by platforms;

- New obligations for very large platforms to take risk-based action to prevent abuse of their systems;

- Wide-ranging transparency measures, including on online advertising and on the algorithms used to recommend content to users;

- New powers to scrutinize how platforms work, including by facilitating access by researchers to key platform data;

- New rules on traceability of business users in online market places, to help track down sellers of illegal goods or services.

The UK’s Online Harms statement identifies a small group of ‘high-risk, high-reach’ services that will be designated as Category 1 services. These will be required to take action in respect of content or activity which is legal but harmful, and to publish transparency reports about their actions. “The regulator will be able to access information about companies’ redress mechanisms in the exercise of its statutory functions, and will accept complaints from users as part of its horizon-scanning and supervision activity.”

Given the context of Brexit, and the UK’s determination to set its own regulatory framework and trade relations, it is striking how similar the proposals are, indeed how influential UK regulatory thinking has been in shaping what is rapidly becoming a global agenda. How to reign in big tech: companies that have highlighted again during the Covid pandemic how indispensable they are to the functioning of our economies, societies – and the creative industries.

There is a tension between the global character of target firms and regulatory divergence. An important distinguishing factor is the fluid character of UK regulation, with many different agencies at the table, and interventions that centre on non-statutory codes of conduct. In our own research on platform regulation for the AHRC Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre (PEC), we have identified the close interplay of multiple agencies on the same object of regulation.

The economic and sociological analysis of the creative industries has long identified the critical role of gatekeeping firms in the production and dissemination of culture. VLOP or SMS: we will need to get used to new gatekeeper terminologies.

This post first appeared on the blog of the AHRC Creative Industries Policy & Evidence Centre (PEC). Prof. Martin Kretschmer leads the PEC’s work on intellectual property, business models & content regulation.