Kerry Patterson, Project Officer for CREATe’s Digitising the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks project describes some approaches and challenges in her efforts to carry out diligent search for thousands of images with little original context.

The enormous visual appeal of the poet Edwin Morgan’s scrapbooks is countered by a large complication for the copyright researcher. Morgan rarely gives a source for the images he uses, meaning that the 16 scrapbook volumes contain tens of thousands of images with no note of their original context. For the researcher performing a diligent search as part of a mass digitisation project, the difficulty is this; without any supporting information for an image, what resources can be used to carry out a diligent search? Do the IPO’s Diligent Search guidelines offer assistance?

Double Page from Scrapbook 12

Background to the Scrapbooks

Morgan’s approach to organising his papers, as held by the University of Glasgow’s Special Collections department, was diligent and specific. Within the scrapbooks, every page is numbered and Morgan cross references across volumes, adding notes when a related item appears on another page. Within his correspondence and papers, references to scrapbook pages also appear.

In the case of complete or substantial newspaper and magazine articles used in the scrapbooks, Morgan usually gives a date and name (or initials) of the source. With images, he may note the name of the subject of a photograph or the title of a painting, but does not do this every single time. Moreover, so abundant and densely crowded is the visual material that it would not be practicable to include the source of every image without disrupting the look of the scrapbooks or embarking on an incredibly tedious recording exercise. With 3,600 pages across 16 scrapbooks and an average of 15 cuttings per page, recording the source of around 54,000 items would have made compiling the scrapbooks a chore. A vital part of the function of the scrapbooks was to address Morgan’s need for creative expression. As an art lover, he would have seen his scrapbooks as working in the 20th Century tradition of fine art collage, as initiated by Picasso in 1912. Morgan was a great admirer of the Surrealist group, which embraced the collage technique and declared “no respect for any academic tradition.” (Read, H (1936). Surrealism. London: Faber & Faber. p45).

IPO Guidelines

The IPO’s Diligent Search guidelines for still visual art have been created in consultation with sector specialists. The Introduction sets out that there is “no set way to conduct a diligent search as this will depend on the information available on the work” and additionally, there is “no set minimum requirement to be followed in every case.” Setting out to be “a non-exhaustive list of additional sources” does reflect that users’ own knowledge about the provenance of and background to the items they are researching will remain important. Prior to starting a diligent search, an applicant should check the UK Orphan Works Register and the Europe-wide OHIM Database. Looking specifically at photographic images, the Orphan Works Register for Still Images shows 212 records and the OHIM database for photography has only 2 works (accessed 02.06.15). These small numbers are not surprising given that the scheme has been in operation for less than a year. The Orphan Works Register does not currently allow the user to search within the 16 categories of Still Images.

As advised by the Guidelines, looking to the provenance of the scrapbook gives a general background to where images may be found. Scrapbook 12, which is being used as the focus of this project, was made between 1954 and 1960. Although Morgan took some material from older sources, we can assume that much of the material is roughly contemporary, between 1950 and 1960. Much older text material is identifiable by typescript (or Morgan’s date notes), and older original photographic images are also recognisable by their format. We know some of the publications Morgan definitely used in Scrapbook 12, such as the Glasgow Herald newspaper, Life Magazine, Doubt Magazine and the Illustrated London News. Familiarity with the format and content of these publications can aid in identifying material from those sources when text is used. But how can it be verified? The guidelines state, “It is important that applicants consult with multiple sources to validate information on a creator.” In the case of printed material in the Scrapbooks, seeing text and images in their original context would be the most important step.

Image Searching on the Web

Accessing original copies of newspapers and periodicals will not be possible for all researchers. The Google News Archive has scans of some newspapers but this is not fully text searchable across all publications, although this capability is in development. A list of all available newspapers can be found here. The News Archive digitisation project has ended, with no plans to add any more publications. Magazines are available separately through Google Books (complete list here) and they do appear to be text searchable. I found that a search of text from a Life Magazine article brought me to the source, while text from the Glasgow Herald newspaper did not. Another known source, The Illustrated London News, is fully text searchable for registered users of the Gale News Vault historical newspaper archive. I was able to access it through the Glasgow University Library website as a staff member, and other organisations will have similar arrangements. While I suspect that some of the Scrapbook images will come from these sources, looking through a decade of material from several publications either online or in a library, on the off chance of identifying an image, is not a task realistically achievable for a mass digitisation project.

Faced with an image with no caption or clue to its context, web searching is often the best place to start and inevitably, it is hard to avoid the wide reach of Google. A text Google search of the contents of a photograph might yield results if it is a well-known image of a famous person, a famous painting or if it shows something particularly unusual rather than ‘a tabby cat’. For image searches, Google allows you to upload an image to be compared to visually similar images. Each image needs to be individually cropped, which will most likely involve extra work in the case of a mass digitisation project. In the scrapbooks, double pages from a 30 page sample have been photographed initially, so these require further editing to produce individual images. In many cases, Morgan has cropped down the cuttings from their original form, and these crops and irregular shaped items decrease the likelihood of an uploaded image search yielding results. It is worth noting that Google’s Help Forum states;

“When you search using an image, any images or URLs that you upload will be stored by Google. Google only uses these images and URLs to make our products and services better.”

This may be undesirable for some users of the service, particularly for a mass digitisation project.

Other search engines are available of course – Bing offers an Image Match service that allows you to upload images. Its privacy statement does not specifically mention what happens to these images. However no other search engine currently has the reach of Google, and the access to such an enormous image bank. For reverse image search, the IPO Guidelines suggest Tineye and PicScout, both of which allow the user to temporarily upload an image for search purposes, as with Google Images. Tineye does not store images uploaded by occasional users but registered users can store searches and make them available to others, which some may find to be a useful function. The Tineye FAQ states:

“Images uploaded to TinEye are not added to the search index, nor are they made accessible to other users. Copyright for all images submitted to TinEye remains with the original owner/author.

Search images submitted by unregistered users are automatically discarded after 72 hours. Links to these searches will stop working after 72 hours, unless a registered user happens to save the same image.”

The Picscout Platform appears to be more aimed at commercial users and I found it to be less useful in identifying images for the purposes of diligent search. Their search tool is designed to “enable image buyers to identify and license the images they’d like to use.” They have “200 million owner-contributed image fingerprints” and as a subsidiary of Getty Images, they would seem to be a good resource for commercial photography.

Scrapbook Examples

So how do Google, Tineye and Picscout perform with examples from the Edwin Morgan Scrapbooks? Throughout the process of gathering information from the Scrapbook I have experimented with additional research on a selection of images, cropping a few examples from each page to subject them the above tools. I have selected 4 examples I found interesting, all of images without any accompanying caption text from the source, or note of the source publication.

From page 2239c (inside cover of Scrapbook 12)

From the style, this painting looks to be out of copyright but even so, there would be a photographic credit attached. Google Images and Tineye were both able to point to sources to identify the cutting as a section of the oil painting Villa Doria Pamphili, Rome (Souvenir d’une Villa) 1838-39 (oil on canvas) by Alexandre Gabriel Decamps (1803-60). PicScout was unable to identify the painting. Despite Morgan’s cropping of the image, the painting is well known enough for there to be enough examples of the image that it is shown as a likely match. As the source is unknown, it will be impossible to identify the copyright holder of the photograph.

From page 2248 of Scrapbook 12

This image of an animal looks to have come from a tapestry. A Google text search turned up nothing as I wasn’t sure what the animal was so could not adequately describe it in words. A Google search using this uploaded image gave a number of results which allowed identification of the tapestry, of which this is a small area. Again, although the tapestry is in the public domain, the photograph of it will not be, but there is little chance of ever identifying the source publication. Tineye linked to one French website which had the same cropped image but no information which would have led to the identification. Picscout had no results. In this example, as before, Google’s access to images led to the success of its ‘best guess’ answer being correct.

From page 2253 of Scrapbook 12

I selected this as a representative example of the better quality photographic material in the scrapbooks. It appears not to be cropped but it is impossible to confirm. There were no result for a text search description of the image, including Scrapbook dates, a basic description and the word ‘Buick’, as it appears on one of the men’s overalls. I would guess that it probably comes from an American magazine, like Life. Google Images, Tineye and PicScout all came up with no results using an uploaded image, although it is the kind of image I might have expected PicScout to potentially recognise, given its coverage of commercial picture libraries.

From page 2265 of Scrapbook 12

For this photograph, Google Images, Tineye and PicScout all came up with no results for a search with this uploaded image. However thanks to Morgan’s additional notes that the subject is artist Yves Tanguy and the date is 1954, Google Image results for a text search of ‘Yves Tanguy portrait 1954’ include the right image, complete with photographer credit (Edward Saxe). The direct image searches were likely affected by the crop of the image, as the portion of the photograph containing Tanguy is only 1/3 of the original work.

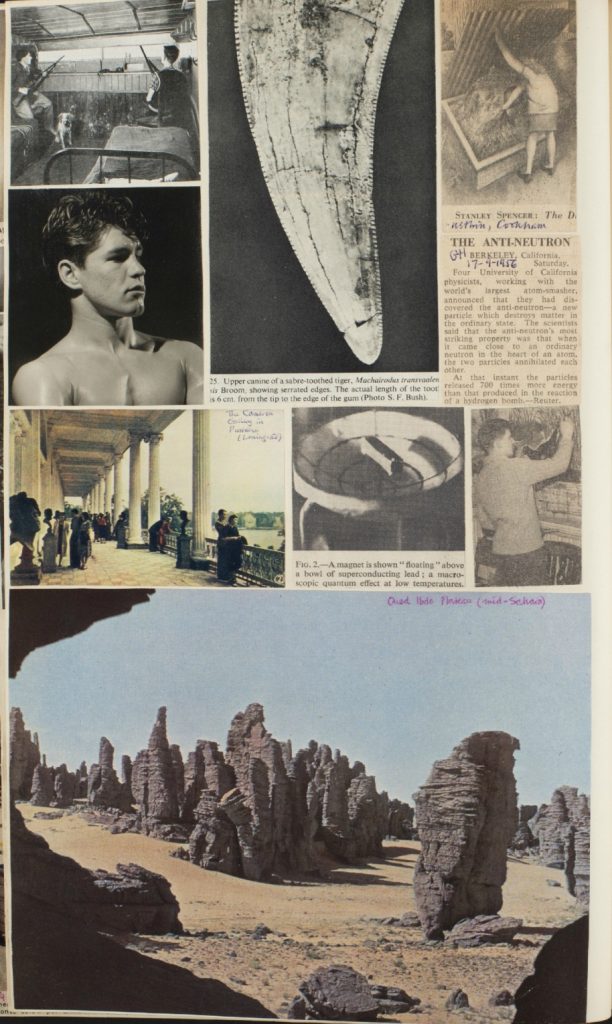

The kind of hit rate you can expect to get from Image Search will of course vary. I selected two pages at random from Scrapbook 12:

Page 2375 had 8 viable images, a mix of types of images in black and white and colour including two artworks. Google Images only helped with the identification of one, the Stanley Spencer artwork, which already had a caption to identify it.

Page 2375 had 8 viable images, a mix of types of images in black and white and colour including two artworks. Google Images only helped with the identification of one, the Stanley Spencer artwork, which already had a caption to identify it.

Page 2435 had 10 images but I only used 8 as 2 were Morgan’s own photographs. Two of the 8 images were very obviously cropped, to the point where they did not show anything discernible but acted more as ‘filler’ images on the page. Google Images identified the Stanley Spencer artwork (again this already had a caption). It also identified the microscopic image as showing poliomyelitis, although the caption from the Scrapbook does tell us that, and the origin of this particular image remains unknown. One interesting outcome came from the image search of the illustration from an advert from The New Statesman (source given in Scrapbook). A number of results came up with the same advert but one identified the copy of the periodical as an issue with spoof publisher adverts and in-jokes. This aspect is fascinating from a collections research point of view, if not helpful for diligent search.

From that small sample of 16 images over 2 pages, I was only able to identify 2 items, both artworks by Stanley Spencer which were already captioned in the Scrapbooks.

Conclusion

Even without the image’s original context, there are ways you can conduct diligent search. Reverse image search platforms can be a useful tool for the copyright researcher, though it is not surprising that well-known art and photographic images get the best results. Image searches work much less well on anything from a more obscure source or which has been cropped too much from its original state. An image search can even be secondary to a well-worded text search if your source image is not of sufficient quality, but additionally it can turn up interesting supplementary information about the item.

On my sample of images, I found that Google provided the best results with Tineye secondary and PicScout unable to provide anything at all. However individuals and organisation may have reservations about uploading large amounts of images to Google Image Search, and it is possibly not included in the IPO Guidelines for this reason. Even with Google the hit rate is still not enormous, with only 2 of 16 images recognised from my 2 page sample, both of which were by a well-known artist. Depending on the source and format of the images you are researching, the preparation of images to upload for search will involve additional time. This is would be a significant amount of time for the 3,600 Scrapbook pages, and potentially for other mass digitisation projects.

The IPO Guidelines are helpful if working from a background without knowledge of visual art and photography. The roundup of resources reflects the due diligence that archivists and collection managers would generally use. The Guidelines state that they provide a “non-exhaustive list” of resources, which is a reminder that in most cases, knowledge of the context of the images will be key in determining appropriate resources to check. The guidelines state that there is no set route for due diligence checking but it is still unclear how diligent to be. Is it diligent or excessive to look through 40 boxes of material? To search 10 years’ worth of magazines?

The most obvious way to answer that question would be to submit an Orphan Works application to the IPO, setting out your research. If you decide to do that, you may be interested in reading Melissa Terras’ experience of making an Orphan Work application through the UK scheme, as described on her blog. The ability to perform a diligent search will depend on time and resources. For example, it seems modest to suggest it would be sufficient to spend an average half an hour on each item to determine copyright or carry out a diligent search. Yet in the case of the circa 54,000 items in the 16 scrapbooks, that would take one person nearly 15 years, working for 7 hours a day, 5 days per week.

In the case of the Scrapbooks, the majority of images are fairly unremarkable photographs, or sections from photographs, taken from the contemporary press. It is Morgan’s use of these images which makes them remarkable, as each item plays only a small part in his overall creative vision. Exploring the matter of diligent search for images without source information inevitably leads quickly to the issues at the heart of the Edwin Morgan Scrapbook Project. Should every cutting be treated the same, whether it is a full newspaper article, a single word from a headline or a section of an image? Ultimately, the project raises the question of how mass digitisation projects can ensure that they comply with due diligence requirements in a manner that is achievable and workable for organisations.