By Steven J. Watson1, Piers Fleming2, Daniel J. Zizzo3

1 Department of Psychology and CREATe, Lancaster University, s.watson3@lancaster.ac.uk

2 School of Psychology and CREATe, University of East Anglia, p.fleming@uea.ac.uk

3 School of Economics and CREATe, University of East Anglia, daniel.zizzo@ncl.ac.uk

After the publication of our review exploring why people download copyrighted materials unlawfully and the impact of those downloads we were invited to contribute to this blog. This work was part of the RCUK Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy (CREATe) and one of the paper’s key contributions was to introduce a robust method for appraising evidence from the medical sciences. One of the common themes during the debate following the release of the paper was the difference in the types of evidence available in the medical sciences compared to the IP realm. This blog considers these issues with a focus upon the systematic review process.

Science, Evidence and Errors

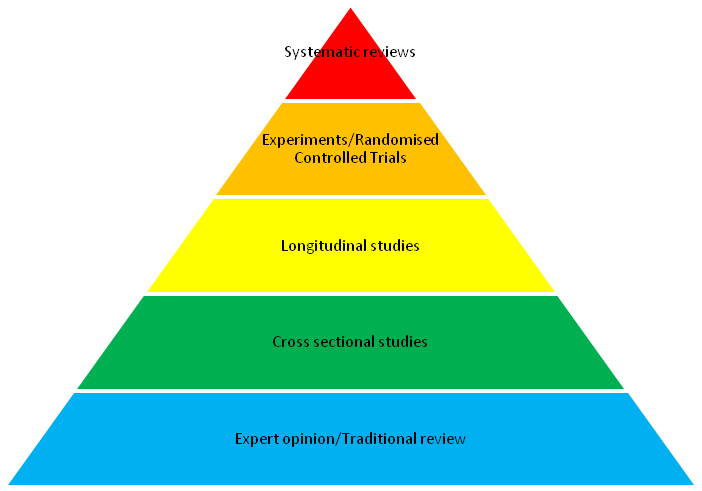

The power of the scientific method is that it is self-correcting; we develop models of the world and then test these models empirically. However, the consequences of persisting with suboptimal models are greater in some fields than others, for example, in medical science an incorrect consensus can cost lives. A rigorous method was needed to describe the current body of evidence in a way that could challenge and correct widely held beliefs. Systematic review filled that need. Without systematic review human albumin (a blood product), which had been used in the treatment of blood loss and burns for over 50 years, would still be used today but we now know that it is not just ineffective, but dangerous1. This ability to overturn a practice that had been considered routine for half a century and literally save lives is why in medicine the systematic review is widely considered to be the highest quality of evidence available (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The pyramid hierarchy of evidence in medicine, with the highest quality evidence for informing action at the top and the less reliable forms of evidence further down the pyramid.

Despite these advantages systematic reviews are not perfect and limitations remain. Notably they can be biased by the tendency for research finding larger and statistically significant effects to be more likely to be published in academic journals. This makes these studies easier for reviewers to find and creates the risk that reviews exaggerate the size of the effects of phenomena. This is known as the “file-drawer’ problem. Of course this same flaw makes the original literature similarly misleading. It can also be difficult or even misleading to try to combine studies that differ widely in their methods. This is known as the “apples and oranges problem” and reviewers must be careful to make sure that the studies they seek to combine are genuinely comparable.

Systematic vs Narrative Reviews

To see why systematic reviews can be so powerful, it is worth comparing them to the traditional narrative review. Typically a review consisted of an expert in the topic discussing and critically apprising a body of literature. However, this process is prone to biases including:

- A preference bias, which describes the propensity for authors to design an investigation so that their preferred outcome is likely to be found. For example, omitting poor quality studies that counter the authors’ proposed view, but including studies that support it.

- An availability bias, which refers to the ease with which associations are brought to mind being used to ascertain their veracity.

- Selective exposure, referring to seeking information congruent with what is already believed and avoiding contrary evidence.

- Confirmation bias, referring to the tendency to misperceive or misremember incongruent information in a manner that supports prior beliefs.

Narrative reviews also cannot be replicated. The process by which particular studies are included or excluded and study results analysed are not described. It is impossible to determine whether studies were excluded because the author did not consider them relevant, because the study presented findings counter to their existing beliefs, or whether they were unaware the study existed.

Systematic reviews seek to ameliorate these biases by a number of mechanisms.

- An exhaustive search with explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria – This ensures all evidence must be accounted for whether it contradicts the researchers prior beliefs or not.

- Reproducibility – All methods are published so others can replicate the review. This ensures the review can verified by anyone that wishes to do so and allows the review to be quickly repeated over time as new evidence accumulates.

- Transparency – Data and references from primary articles are published for external scrutiny. Thus if any bias is evident within a review or if there are errors made these can be corrected.

Combined these three elements reduce as far as possible the introduction of bias, and mean that any failings that remain can be identified and the self-correcting nature of science is restored to the review process.

Systematic Reviews in IP research

There are however some clear practical difficulties in applying these kinds of methods to IP research. In medicine there is a standard research method for testing hypotheses – the clinical trial. Thus in a systematic review the evidence that is being combined is usually testing the same hypothesis in a very similar way. This is rarely the case in the IP realm. Our file sharing report found a variety of different methods used to assess the impact of unlawful file sharing such as surveys, sales data, or monitoring activity on infringing sites. When studies methods and outcome measures are very different, it is not appropriate to directly compare or combine their outcome estimates as if they are measuring the same thing (the “apples and oranges” problem).

The second problem is that there may not be a clear comparator, unlike medicine where two types of medicines are quite easily compared. For example, it is not feasible to compare sales in the presence of file sharing to sales if file sharing was impossible. Attempts to do this have focussed upon cross-country comparisons at moments file sharing becomes easier (e.g. the introduction of p2p) or harder (e.g. a new law is introduced or a major file sharing site is closed down). These cross-country comparisons are imperfect controls and the choice of how file sharing and sales are measured and what additional factors are controlled for in analysis impacts upon the conclusions drawn.

The third problem is that the topics of interest keep changing. Our file sharing report explored downloading unlawfully but streaming is an increasing concern. However, while the methods people use to engage in different infringing practices may change, the reasons why they may do them are likely to be considerably more stable.

A Flexible Review for IP Research

Scoping reviews seek to maintain as much of the rigour and transparency of systematic reviews as possible, but permit greater flexibility to account for the kinds of difficulties encountered in data described above. The aim becomes less to directly test a hypothesis such as “Is file sharing bad for society?” but instead to appraise “What sorts of approaches have been used to address this problem, and what are the common themes that cut across these different approaches?”. Thus the method allows us to identify strengths and weaknesses in a body of evidence to determine where more research is required to answer outstanding questions.

Scoping reviews are especially good at generating theory based on a large swathe of empirical evidence. Therefore even as technology changes it is possible to develop predictions based on prior theory and, where required, amend or improve upon that theory as the world moves on and evidence changes. Most significantly these predictions allow the developers of legal services to design and test new modes of content delivery that will appeal to specific groups of infringers and convert them into customers. Looking back to develop sound theory is not a waste of time; to cite one of psychology’s great pioneers Kurt Lewin, “there is nothing more practical than a good theory”.

1. Cochrane Injuries Group. Human albumin administration in critically ill patients: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 1998; 317(7135): 235-40.

—

Additional note: A related CREATe working paper by Ruth Towse (CREATe Fellow in Cultural Economics, University of Glasgow and Professor Economics of Creative Industries, CIPPM, Bournemouth University) was published on 4 August 2014:

Literature reviews as a means of communicating progress in research

—