Post by Liz Dowthwaite (Doctoral Researcher at CREATe & Horizon, University of Nottingham)

Figure 1 Internet culture as portrayed by the webcomic ‘Nedroid’ on Tumblr [2]

My preliminary questionnaire

In order to begin examining of social media use in the webcomics community, I have so far attended three UK Comic Conventions [10,11,12], and have interviewed 11 creators about their experiences with social media, copyright and IP, and crowd-funding. I also compiled a questionnaire to probe website and social media use amongst readers and creators, and have preliminarily analysed 202 responses (the questionnaire remains live if you are interested in taking part). Respondents were split into two groups: ‘Creators’ who also create comics (90), and ‘Readers’ who do not (112). Readers tend to read more comics than creators, but over a quarter of both groups regularly read more than 21 titles. Most creators had been maintaining their current webcomic for 2 years or less, have created 1 comic, and update once a week. Around 15% receive more than 5000 unique visitors a week and 6 of them consider themselves to make a living wage. Creators and readers make use of many different websites to engage with each other in different ways, and almost without fail (after the comics own website) the most used sites are social media sites: Twitter, Facebook and Tumblr. Reddit, Google+, DeviantART, Pinterest, Instagram were also mentioned relatively frequently.

So how do webcomics artists get paid?

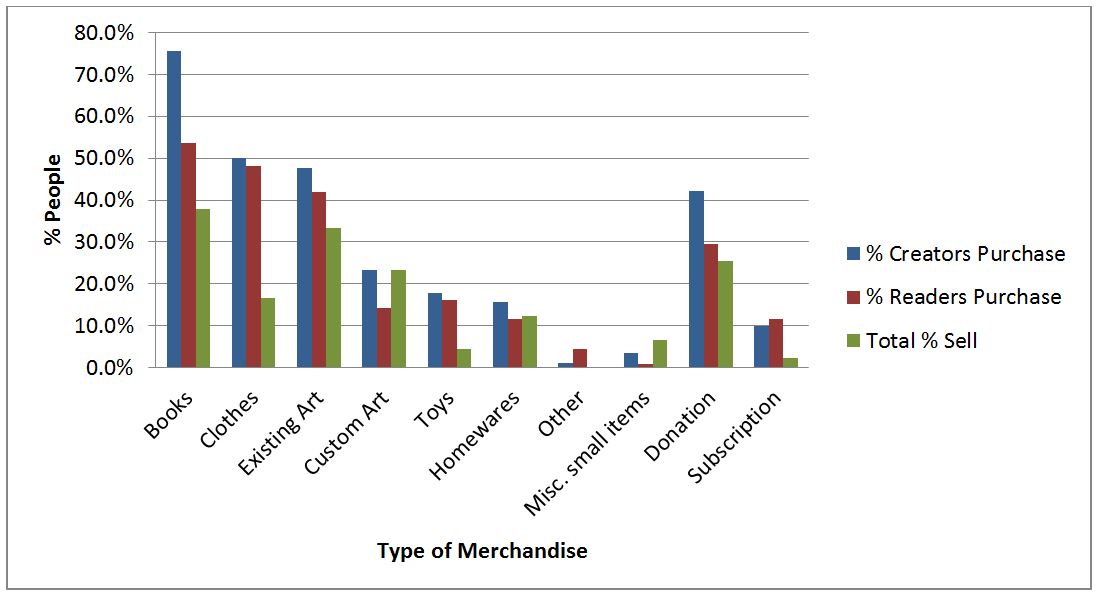

The basic webcomics business model is “to offer free-to-the-consumer, ad-subsidised content, which then trades on audience loyalty by selling books, t-shirts, merchandise and original art” (P.121) [4]. This audience loyalty is cultivated through social media. As well as advertising and merchandise, a third, related, business model is emerging which I think of as ‘patronage’, where artists run Kickstarter campaigns (for merchandise) or invite readers to donate money (either one off payments or subscriptions) whilst their comic content remains free-to-view. Surprisingly, only half of the creators who responded sell any kind of merchandise; the most common types of merchandise sold are books and artwork. Most respondents have however bought merchandise of some kind; more creators than readers have done so, and the majority of this difference comes in book purchases. Custom Art does not appear as popular as existing art, potentially because of the typically high costs to purchase and ship; original existing art is also often high in price (around $100 for an original page is not uncommon), but prints can often be bought much cheaper. It is interesting that people buy book collections and prints of comics that they have already read for free online, especially as it can be assumed that books may include e-books. Clothes are also a very popular purchase; this is potentially related to a desire to be part of a ‘niche group’ – only those who also read the comic are likely to recognise a t-shirt based upon it. Further analysis of this buying and selling behaviour would be interesting. It is my belief that readers who are more engaged with webcomics creators through social media will spend more money on a comic and buy more items.

Some webcomics also invite people to donate money (one-off or recurring payments), or provide access to the creators’ Amazon Wishlists should readers be feeling generous. Many artists self-publish books and may fund their efforts through sites such as Kickstarter; Dresden Codak artist Aaron Diaz funded the printing of his first book within an hour, ending with 1783% of his target amount from over 7500 backers [13]. Many other webcomics-based projects are also getting funded this way, including games, toys and figurines, animated shows, and entirely new comics; practically every webcomic-based Kickstarter campaign has succeeded (often massively over-target). At the time of questioning, only around a quarter of the creators said that they take donations, and a much smaller percentage offered subscriptions, however since then Patreon (a patronage/subscription platform for creators and artists) has become highly popular in the webcomics community and so these numbers may not be representative. The relatively high percentages of respondents who have paid a donation or subscription suggests that readers are quite happy to ‘reward’ an artist that they feel deserves it, and to pay for things they already receive for free (as with books and artwork). It is also interesting to note that creators seem more willing to donate (or subscribe) to their fellow artists, whilst not asking for donations themselves.

Figure 3 Comparison of buying and selling behaviour

It is fascinating that an increasing number of artists are able to support themselves full-time using the merchandising and donation models described above. Going forward, I am interesting in investigating whether there are significant links between social media use, reader engagement, and this ability to ‘monetise’ a free-to-view work. From speaking to artists and my own experiences with webcomics, it seems to me that social media allows artists to interact with their readers more meaningfully, and in turn this makes them more likely to spend money. My next step is to analyse more fully the interview data I have collected, looking for these links, and documenting the different types of interactions that occur in these communities across social media. I hope to be able to conduct further studies into crowd-funding and monetising work in relation to social media, including some case studies of Kickstarter and Patreon. I also hope to be able to look at some of the issues raised by the artists from the readers point-of-view.

- Allison, J. Post Webcomics. A Hundred Dance Moves Per Minute, 2013. http://sgrblog.blogspot.co.uk/2013/03/post-webcomics.html

- Clark, A. Nedroid Fun Times, The Internet. Tumblr, 2013. http://nedroidcomics.tumblr.com/post/41879001445/the-internet

- Fenty, S., Houp, T., and Taylor, L. Webcomics: The Influence and Continuation of the Comix Revolution. ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies, 2004. http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/v1_2/group/index.shtml

- Guigar, B., Kellett, D., Kurtz, S., and Straub, K. How to make Webcomics. Image Comics, Berkeley, CA, 2011

- Jacques, J. Comics comics comics. LiveJournal, 2009. http://qcjeph.livejournal.com/100732.html

- McCloud, S. Understanding Comics: the invisible art. HarperCollins, New York, 1993.

- Rohac, G. Copyright and the Economy of Webcomics. 2010.

- Watson, J. Four year experimentaversary. HijiNKS Ensue – A Geek Comic, 2012.

- Watson, J. The Comic, The Experiment, The Whole Story. HijiNKS Ensue – A Geek Comic, 2013. http://hijinksensue.com/experiment/story/

- Nerd Fest Comic Con. 2013. http://web.archive.org/web/20130428074127/http://www.nerdfestcomiccon.com/

- The Lakes International Comic Art Festival. 2013. http://www.comicartfestival.com/

- Thought Bubble – The Leeds Comic Art Festival. 2013. http://thoughtbubblefestival.com/

- The Tomorrow Girl: Dresden Codak Volume 1 by Aaron Diaz. Kickstarter, 2013. http://www.kickstarter.com/projects/156287353/the-tomorrow-girl-dresden-codak-volume-1?ref=live